|

Dredging up the past in Lakeport, CA On a recent trip to Oregon, my husband and I stopped in Lakeport, a charming 19th century town that looks like it has been frozen in time since the1950s. It was a sunny Saturday morning, and there was a vintage Volkswagen car show going on in the public park that lines the shore of Clear Lake. We had lunch with a view of people boating and fishing and talked about Eric’s family ties to the area, including his mother learning to waterski on that very same lake in the 1950s. Unfortunately, it’s not a good idea to swim in the lake or eat the fish caught in it. Belying its name, cinnabar mining throughout the area in the previous century has left Clear Lake poisoned with mercury. Being the nerdy historians we are, we paid a visit to the local historical museum located in the restored courthouse. The plaque outside the building noted that the courthouse was the site of the trial for the infamous “White Cap Murders” in nearby Middletown that shocked the country in 1890. We had never heard of them. The men convicted are, clockwise from top left, C.E. Blackgurn, Charles Osgood, Robert Cradwich and B.F. Staley. The murder and trial made headlines across the country. See more. On further exploration, we learned that nearly a dozen men, dressed in the white hoods favored by lawless groups in the 19th century, had taken advantage of a local candidate’s ball one October night to storm what was usually the crowded Campers Retreat saloon. They shot and killed the proprietress, Mrs. Riche, fatally injured her husband, and nearly killed employee Fred Bennett, their true target, who they had planned to tar and feather and run out of town. Apparently, many of the men—miners at the nearby quicksilver mines—held a grudge against Bennett for his treatment of them at the saloon. Later investigations showed that a wealthy mine owner with competing interests with Bennett had perhaps whipped them up to do the deed. He himself remained unpunished while four men were sent to San Quentin prison. The Lake County Courthouse today. It is now a museum. The violence was considered extreme, even for an area with a Wild West mentality, and we wondered if the fact that the men were mining quicksilver—or mercury—could have contributed to their actions. Mercury is a neurotoxin, and long-term exposure can lead to, among other symptoms, mood swings, irritability memory problems, difficulty concentrating and, in extreme cases, psychosis or hallucinations.

Learning more about the history of the lands where we live, work, and play is an urgent imperative today, a time when we’re finding toxic microplastics in the snow on Everest, in the depths of the oceans, and in our own bodies. Fertilizers and pesticides have been linked to neurological disorders like autism and Parkinson’s disease. I shudder to see children playing in the creek that empties onto our local beach, creating a little pond. The creek passes through farmland, gathering toxins on its way to the ocean. We all might benefit from being a bit more curious. Sources There’s plenty to find on the internet about the White Cap Murders, but I found this document, to be the most well-researched and thorough.

0 Comments

The Legacy of the Dust Bowl Because of his role running an incubator/accelerator for startups focused on resiliency in the face of the changing climate, my husband recently took a tour of a local research farm called Pie Ranch. Pie Ranch practices regenerative agriculture, which is intended to restore and maintain healthy soil ecosystems on farmland. Some regenerative farmers don’t till the soil at all (it releases carbon into the atmosphere and dries out the soil), but at Pie Ranch they’ve discovered that shallow tilling every few years lets native plant roots survive and thrive, allowing grazing cows and roaming chickens to add natural fertilizer to the soil. These practices are very different than the farming protocols that contributed to conditions in the Dust Bowl in the 1930s, when massive storms of dried out soil, called “black blizzards,” blanketed the states in the Great Plains and even turned day to night in places as far away as Chicago and New York City. Unusually rainy years in the 1920s had encouraged people to take advantage of the cheap prairie land the US government was selling. Many believed the dry years were permanently over, buying into the erroneous real estate slogan that “rain follows the plow.” With a poor understanding of the ecology of the region, many farmers plowed deep with the help of new machines. They killed the roots of the native grasses that served to trap soil and hold water. So, when drought conditions returned in the 1930s, the ubiquitous winds blew the topsoil away, destroying ecosystems, livelihoods, and lives. Photo by Dorothea Lange, 1938. https://www.loc.gov/resource/fsa.8b32349 The Dust Bowl affected 100 million acres, mainly in the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas. Everyone who has read John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939) knows that people were forced to emigrate to other parts of the country in search of work that was hard to find during the Great Depression. The federal government stepped in with programs to halt soil erosion and introduce conservation practices, but by the 1970s, big agricultural companies were using destructive methods that included draining aquifers for irrigation and the intensive use of pesticides and fertilizers.

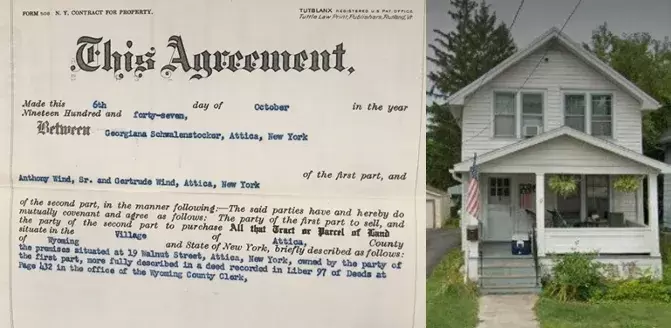

We’ve been slow to learn from the lessons of the Dust Bowl. In the US, less than five percent of farms use cover cropping (a regenerative strategy), and we’re losing our soils ten times faster than they are replenished. We need more farmers farming like Pie Ranch, and we need it fast. Sources: Earthday.org National Drought Mitigation Center: https://drought.unl.edu/dustbowl/ Soil Health Institute Wikpedia: Dust Bowl Main image caption: A dust storm approaching Rolla, Kansas, May 6, 1935. (Image: Franklin D. Roosevelt Library Digital Archives) https://drought.unl.edu/dustbowl/ The legacy of the Attica prison uprising A branch of my family has lived in Attica, NY, for 80 years. Less than a mile from the small, bucolic upstate town is the maximum-security prison that’s (in)famous for an uprising where 32 prisoners and 11 hostages were killed during the violent retaking in September 1971. My maternal great-grandfather was a plumbing instructor at the prison in the late 1940s, after moving to Attica when he retired. My mother and her siblings remember that the town had an ice cream store and a movie theater and that their grandparents’ house—at 19 Walnut Street—had an outdoor pump with refreshing icy cold water. She remembers that her dad avoided driving past the prison on the way in to town. The deed for the Attica house for which my maternal grandparents paid $7,000 in 1947, and the house today. Given this personal history, I was interested to read Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy, a 2016 Pulitzer-prize winning book on the prison uprising by Heather Ann Thompson. Growing up, I remember hearing the event referred to as a “riot,” so I found the difference in terminology particularly interesting. The uprising stemmed from the inhumane conditions at the prison, which was overcrowded with mostly Black and Puerto Rican prisoners, some of whom were incarcerated for issues as minor as breaking parole after a teenage joy ride. Others were hardened criminals and/or inmates who had participated in earlier uprisings in other prisons. The inmates suffered from inadequate and poor food, minimal exercise, frequent isolation, brutal and indifferent doctors, and daily mistreatment by racist corrections officers, just to name a few grievances. During the hot summer of 1971, the commissioner of prisons failed for months to respond to the inmate’s letter asking him to address conditions, and after an incident where two inmates “disappeared” following an altercation with guards, tensions were high. When some of the inmates realized they were trapped in a tunnel leaving the mess hall and were not going to the yard for exercise as was usual, and faced with the head guard responsible for the disappearances, they panicked, fatally injuring a guard and taking 42 staff hostages. The inmates immediately elected a diverse group of leaders, established a security detail for the hostages, enforced their own rules, and stocked and staffed a medical station. They then asked for the prison authorities to bring in a group of outside negotiators. During three days of negotiations, the authorities agreed to meet many of the prisoner’s demands for better treatment. They also laid plans to retake the prison by an overwhelming force, arming NYS troopers with weapons outlawed by the Geneva Conventions and (illegally) failing to track who was receiving them. When Governor Nelson Rockefeller gave the OK, officials blasted the inmates and hostages with immobilizing tear gas and followed it up with a barrage of bullets. Ill-prepared state troopers and guards killed 10 of the hostages and 32 prisoners.

Coverups, deliberate sabotage of the many investigations into the uprising, and threatening of coroners and undertakers began immediately. “Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth,” is an idea attributed to Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels. During the uprising, officials immediately began feeding lies to the journalists covering the event. They made up stories about prisoner abuse of hostages and claimed these were new types of dangerous “radical, militant prisoners.” In truth, the inmates had gone out of their way to protect the hostages, providing mattresses and blankets, medical care and food. In a few cases, the inmates literally took bullets for them during the retaking. None of the hostages were killed by prisoners. Buffalo Evening News headlines on September 13, 1971. “Rocky,” Governor Nelson Rockefeller, blamed the inmates for the bloodshed he authorized after refusing to talk to the prisoners about problems at the prison. Decades-long lawsuits recounted the horrors inmates suffered at the hands of vengeful corrections officers, both in the immediate aftermath of the retaking, when they were beaten and denied care for their wounds, and in the ensuing months when they were subjected to physical and mental torture.

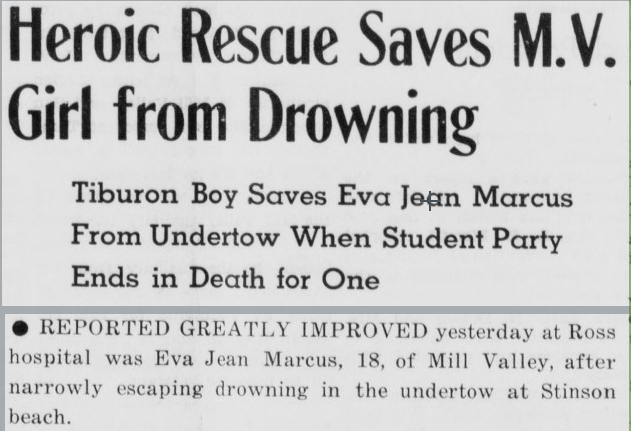

But, although reporters tried to walk back the horror stories when the truth came out, it was too late. Attica was used to justify some prison reforms (many short-lived), but also a massive backlash that resulted in harsh “tough on crime” laws and punishments that directly led to our current overcrowded conditions and the disproportionate incarceration of Black and brown men. And Attica itself is now worse than ever. Warren, Sara, and Marshall Plamondon, 1935 When research proves you wrong One of the things that I love about studying history is the thrill of uncovering a new fact or story. It’s even more satisfying if the new fact or story confirms your own theory or hypothesis. The flip side is that sometimes you are proven wrong. That can range from being merely disappointing to deeply disturbing, depending on the stakes. I’ve always wondered how many graduate students writing dissertations or academics researching books have quietly ignored evidence that disproves their thesis. We’re only human, right? In writing this blog about a real-life hero, I discovered that the thesis that prompted my research was probably wrong. It all started with a conversation with my stepkids (see “Origin Stories” below) that made me wonder to what degree a family member’s behavior can affect a descendant’s behavior. The study of epigenetics even shows that an individual’s lived experience can influence the behavior of their genes. I’ve been told by various family members that my father-in-law, Jim (who is now 91 years old), despite living close to the Pacific Ocean for his entire life, never went to the beach and doesn’t like to swim. I thought this was odd, especially since he had served in the Navy. But after that Thanksgiving conversation, I remembered that I had also heard that Jim had an uncle who died young while rescuing someone from drowning. Ah ha! I thought—Jim’s aversion to the beach and swimming was perhaps instilled in him by traumatized family members when he was a child. I set out to learn more about the circumstances of the tragedy. Thanks to the California Digital Newspaper Collection, which provides searchable records of a huge swath of small local papers, I was able to gather not only the facts around that event but something of a profile of Marshall Plamondon—the younger brother of Jim’s mother. Marshall and his twin brother Warren were born on September 13, 1919, just north of San Francisco, and attended Mt. Tamalpais high school. As a blue-eyed, brown-haired freshman, Marshall was 5’6” tall and 132 pounds. Football was his favorite sport, but he also ran track and played basketball and baseball. He had met a girl he liked. Eager to travel, he aspired to attend Annapolis and become a naval officer. Marshall went on to become a star athlete and class president and make the dean’s list with four As. After graduation, he did not go to Annapolis but instead to nearby Marin Junior College, where he continued his student career as a sports star and class president. Mill Valley Record, May 14, 1940 On May 9, 1940, when Marshall was 20, he and a group of students went to Stinson Beach after classes. While he was walking in the water with Eva Jean Marcus and Donald Ballard, all three were caught by an undertow and pulled away from the beach. Apparently, Marshall helped Eva stay afloat until, exhausted, he passed her off to Ballard and disappeared under the waves. Ballard and Eva eventually made it back to the beach but were unconscious and had to be resuscitated. Marshall’s body was never found. A year later, a memorial bench was placed in his honor on the college campus. Eva Jean, a Mill Valley socialite, went on to marry a lieutenant-commander in the Navy who had survived Pearl Harbor. They had at least two children and Eva died at the age of 73 and her husband at 92. Donald Ballard went to UC Berkeley, moved to Eureka, where he worked at a bank, and was married in 1931.

The tragedy happened only three weeks after Marshall’s father had died of heart failure and three days before my father-in-law Jim’s 8th birthday. Jim’s mother, Sara, was six years older than her twin brothers and had helped raise them—she once told Jim, that she felt responsible for them, more like a mother than a sister. She had also adored her father. Four years after Marshall drowned, the youngest brother, who became a Marine, was killed in the Pacific during WWII. This was enough to traumatize anyone, I thought, and certainly enough for Sara, a young mother still in her 20s, to pass along a dread of loss in the form of an aversion to the beach and swimming to Jim. Then my theory began to fall apart—even if I had conveniently forgotten Jim’s time in the Navy. Jim recently wrote a memoir for the family. In it, he notes that his mother suffered from ulcers (evidence of stress from trauma? I wondered, still hanging on to my theory) and began to have epileptic seizures in her early 30s that restricted her activities (it’s getting harder to hold on to my theory at this point). Jim wrote that his father was a rather cold man, a hard worker, who didn’t believe in vacations and rarely spent time with Jim (my theory is fading fast). Finally, a few pages later, I read that Jim did in fact go to the beach when he was in college. And, I belatedly recalled that he had been happy to attend our wedding on Pescadero Beach. Quite disappointed (I hope to reach the point soon where I’m glad that my lovely father-in-law avoided a lifetime of trauma!), I let go of my theory. Personal branding is nothing new After opening a new hire search at work recently, I spent hours culling through carefully curated profiles on LinkedIn and online portfolios. We’re all familiar with our friends’ and families’ Facebook pages and Instagram posts. Consciously or not, everyone is building a brand—associating themselves with particular people, products, and organizations. I once observed a social studies classroom where the teacher instructed students to create a social media presence for George Washington. The effort to curate a personal brand would not have been foreign to him. Although branding might seem like a phenomenon that started with the rise of social media, the truth is that people have been branding themselves for much longer than that. For instance, Washington and the other Founding Fathers and Mothers paid close attention to their reputations and the causes and colleagues they associated themselves with. Washington aspired to belong to the Virginia gentry and strove to convey gentility and refinement. As a youth, he copied a list of 110 precepts from The Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation and became obsessed with deportment and self-control. He took advantage of circumstances that arose with a dramatic flair, whether it was winning the hand of wealthy widow Martha Dandridge Custis or showing up at the Continental Congress in full military uniform and escorted by 500 riders while modestly insisting he wasn’t seeking a commission. Women of the era also carefully associated themselves with behavior that would accord them high status in their domestic sphere as good wives and mothers and exemplary housekeepers. “Duty” was their watchword, and it might include supporting a righteous cause. Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren’s correspondence demonstrates how eager they were to be seen as committed revolutionaries. Both considered British historian Catharine Macauley—an outspoken supporter of the colonists—to be a mentor and strove for her approval. Martha Washington spent winters encamped with George and the army, self-consciously dressed in American-made homespun as she cared for the soldiers. Likely inspired by Martha, Esther Reed, wife of a prominent revolutionary, penned “Sentiments of an American Woman” in 1780, driving a popular movement for women to wear simpler clothes and less elegant hairstyles and donate the savings to the troops. Just as it does today, one’s public character—one’s brand—mattered. As historian Joseph Ellis notes about the infamous duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr: “Eventually the United States might develop into a nation of laws and established institutions capable of surviving corrupt or incompetent public officials. But it was not there yet. It still required honorable and virtuous leaders to endure. Both Burr and Hamilton came to the interview because they wished to be regarded as part of such company.” Thomas Jefferson and John Adams’ correspondence at the end of their lives was also self-consciously designed for posterity. With every letter, they promoted their personal brands as honorable and virtuous leaders of the new nation. Later in his life, Washington returned to his letterbook to correct spelling and syntax errors. Branding didn’t end with the founders. In 1860, The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness guided women who aspired to be seen as a member of the “right crowd.” In 1936, Dale Carnegie published the still best-selling How to Win Friends and Influence People. And, when I was growing up in the ‘80s, middle-class white people aspired to model Eastern elites as described in the tongue-in-cheek Preppy Handbook.

But no matter what brand we’re trying to convey, we should all realize that our personal history of our actions over time—intended or no—comprise our brand. And, just as product brands suffer when companies are caught lying, so are people punished when the brand they are trying to convey doesn’t align with past actions. (Think Virginia ex-governor Ralph Northam who apologized for wearing black-face at a Halloween party and posing for a photo with someone dressed in a Ku Klux Klan outfit in his younger years.) It’s necessary to see many, many years of consistently better actions before we can trust that the brand has truly learned from the past and cleaned up its act. Sources consulted Bryant, Jessica. Homespun: The Economic Impact of Women on the American Revolution. https://www.frauncestavernmuseum.org/homespun Joseph J. Ellis, Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation (Vintage Books: NY, 2000). Joseph J. Ellis, His Excellency George Washington (Vintage Books: NY, 2004). Cokie Roberts, Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation (HaperCollins: NY), 2004. Main image credit: https://medium.com/ablii/how-to-build-your-personal-brand-as-an-entrepreneur-8addba3ddc9 Indigenous People, Past & Present

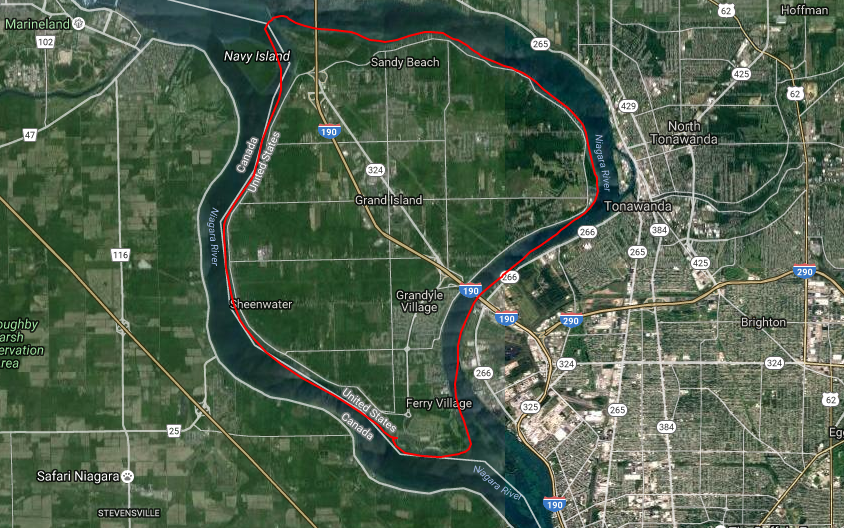

Last week, in a lunchtime discussion on diversity, my colleagues and I talked about the gaps in our K-12 education. We realized that no one had ever heard of the Tulsa race massacre until recently. American slavery had been treated primarily as an economic issue. California state history was taught as a linear progression—first there were the Native Americans, then the Spanish, then the Mexicans, and then the gold rush. In my middle school New York State History class, we watched the 1977 movie The Last of the Mohicans, which literally portrays the end of a race. But Indigenous people are still here. They are not a closed chapter in the history books. I was reminded about a case near my own hometown of Buffalo, New York. Grand Island (image above), and a series of smaller islands, sits in the middle of the Niagara River and was once home to the Seneca Nation. Everyone in the area is familiar with the Seneca Reservation—“the Res”—where you can buy tax-free cigarettes and gas. In 1993, the Senecas sued the State of New York to try to recover the islands. The basis of the suit rested on the 1792 Non-intercourse Act, a law that said you could not have a treaty and take land from an Indian without federal government approval. But that was exactly what New York State did in the Treaty of 1815. I remember hearing that people who lived on the Island were upset that events from so long ago might disrupt their lives. Disbelief and anxiety mixed with confidence that the case would be dismissed. Worries about the case sent property values plummeting, and many of the historic old homes on the island were put up for sale. People asked where the limits were if the Senecas won the case. Would the US cease to exist if all such claims were honored? Then the US Department of Justice joined the fray—against the landowners, noting that, "The Seneca Nation has an historical and federally protected interest in this land… New York State violated federal law when it purchased the land without Congressional approval in the early nineteenth century. It is time to right this wrong." But, in a strange twist, this was apparently a maneuver to shield current landowners from liability. A representative of the Attorney General wrote, “At the outset, we agree that private landowners should not bear any potential liability in the Indian land claims in New York State. The private landowners purchased their land in good faith from New York or from earlier good faith purchasers and therefore should not be subject to Liability or bear any burden in defending these claims.” The judge agreed with them. In 2002, Federal Judge Richard Arcara rejected the land claim for Grand Island filed by the Seneca Nation of Indians. He essentially said that Great Britain’s land grab passed on title to the new United States after the Revolution. If that wasn’t enough, even if that title could be rejected under the Non-Intercourse Act, then a 1784 Treaty effectively extinguished the Seneca’s claim. Here’s the legal jargon: The Seneca Nation’s aboriginal title to the Niagara Islands, if in fact the Senecas ever held such title, was extinguished prior to New York’s purported purchase of the Islands in 1815. In 1764, pursuant to treaty, Great Britain extinguished any claim of Seneca title to the Islands, thereby securing fee simple absolute title to the Islands for itself. Upon the American Revolution. Britain’s fee simple absolute title passed to the State of New York. Furthermore, pursuant to the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the United States again extinguished any claim of title the Senecas may have had to the Niagara Islands. Under the Articles of Confederation and the law of Indian land tenure, once the Senecas’ title was extinguished, New York, as the holder of the right of preemption, obtained fee simple absolute title to the Islands (assuming of course that New York did not already possess such title as a result of the 1764 treaties). There is some evidence that the Seneca chiefs who signed the 1784 treaty were hostages. But no one in the Grand Island case seemed to care about exploring the implications of that for their descendants’ land claims. Similar Indigenous land claims in other states have been resolved through negotiation and the states and federal government have reached agreements that compensated tribes and eliminated questions about the land title of present-day owners. I’m sorry my hometown didn’t do better for our Seneca neighbors. Sources http://isledegrande.com/senecainfo.htm https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/1998/March/129.htm.html https://www.nytimes.com/1993/08/26/nyregion/seneca-nation-files-suit-to-reclaim-grand-island.html#:~:text=The%20Senecas%20claim%20that%20New,the%20attorney%20representing%20the%20tribe. https://www.thehypemagazine.com/2018/01/seneca-evidence-doesnt-add-up/ The DNA of Ancestry

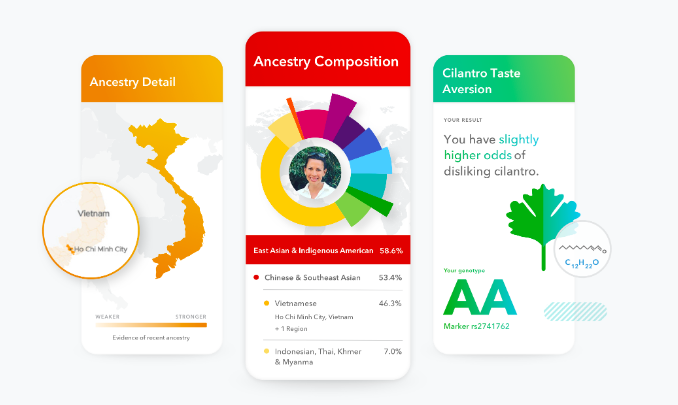

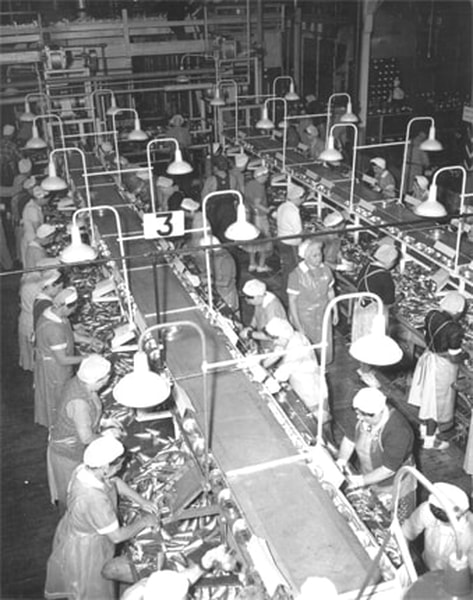

When my dad turned 80 a few years ago, I gave him a 23andMe genetic test for fun. His DNA report said he is 100% northern European, primarily from the Alsace region of Europe, an area along the Rhine River that has fluctuated between German and French control in the last 150 years. The results matched what we already knew about his ancestry from family lore—there were no surprises except for a small but significant percentage of DNA from the Netherlands. For others, genetic testing can be full of surprises. One woman I know learned that the man she calls her father is not actually her father. After taking a DNA test, she discovered her biological father’s family and a number of half-siblings. When confronted with this information, her mother reluctantly admitted to a long-ago affair. Another acquaintance told me she knew she was adopted but not that she also has a number of siblings, which she discovered when she took a test. After the initial shock, these women now appreciate their new connections. For a historian, the idea that we could possibly discover lost or unknown linkages between people and places through a simple test is exciting. We spend a lot of time trying to find tiny bits of information in vast archives, imagining the stories that might lie behind an artifact, and dealing with frustration at the limited documentary sources remaining or photographs that no one thought to label. Taking the guesswork out of our origins feels too good to be true. And, to some degree it is. Because there are other ramifications of the technology to consider. Think about the people whose DNA helps to capture criminals who left their own DNA behind at a crime scene. Revelations about those kinds of shared origins could hardly be celebrated beyond appreciating that a criminal might have walked free if not for the test. For Black Americans, DNA testing can be problematic. DNA tests like those used at 23andMe use reference groups—people alive today who share genetic sequences common to people of a certain area—to deliver results. A function of who is taking the tests, the reference groups are much more robust for people from North Atlantic European populations than for those from other parts of the world. For people of African descent, the reference groups are sparse. But, due to historic abuses by government and health officials, such as the notorious Tuskegee syphilis experiments, Black Americans may be reluctant to participate. This means that they won’t have access to the health data encoded in their DNA that could provide helpful—even potentially life-saving—information. Further, receiving a DNA report that includes percentages of white DNA that might be the result of coercion or rape, could be difficult to deal with emotionally. Recently, two Stanford researchers developed a model to estimate the average number of genealogical ancestors from African and European source populations for a random African American individual born between 1960–1965. They discovered that, on average, there would be 314 African and 51 European ancestors. (Read the article here.) It’s important to understand that all DNA information is probabilistic. That means that even if your DNA test says you are likely to have curly hair, you may not. While DNA revelations can still be exciting, perhaps we should think about what these tests seem to reveal with a deeper understanding of what they don’t. Image: 23andMe ancestry report homepage example. The Monterey Bay Aquarium, https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/about-us The Monterey Bay Aquarium Last week, my husband and I played hooky and took a day trip to the nearby Monterey Bay Aquarium. It’s an amazing place, full of breathtaking displays of the otherworldly life in tide pools and the open ocean. We particularly enjoyed watching the sea otters work their food out of plastic puzzles intended to keep their paws flexible and engage their minds. We touched a sea urchin, marveled at a transplanted kelp forest, and assigned anthropomorphic feelings of depression to Gerry, the only uncoupled penguin. The aquarium is located at the end of cannery row, an area made famous by local writer John Steinbeck, whose tiny cabin is located just a stone’s throw from today’s museum. Though today, the area is billed as full of “luxurious waterfront hotels, enticing restaurants and captivating boutiques,” Steinbeck’s work reminds us that the area was once teeming with corrugated fish canning factories, where a largely immigrant population worked. Workers in a cannery, https://canneryrow.com/our-story/the-canneries Starting in the early 1900s, a spike in demand for canned sardines during World War I sparked the growth of a boomtown that slowed during the Depression and was revived again for World War II, just long enough to decimate the sardine population, sending the area into ruin. Restoration and revival efforts resulting in the tourist-friendly attractions that are there today began in the late 1960s.

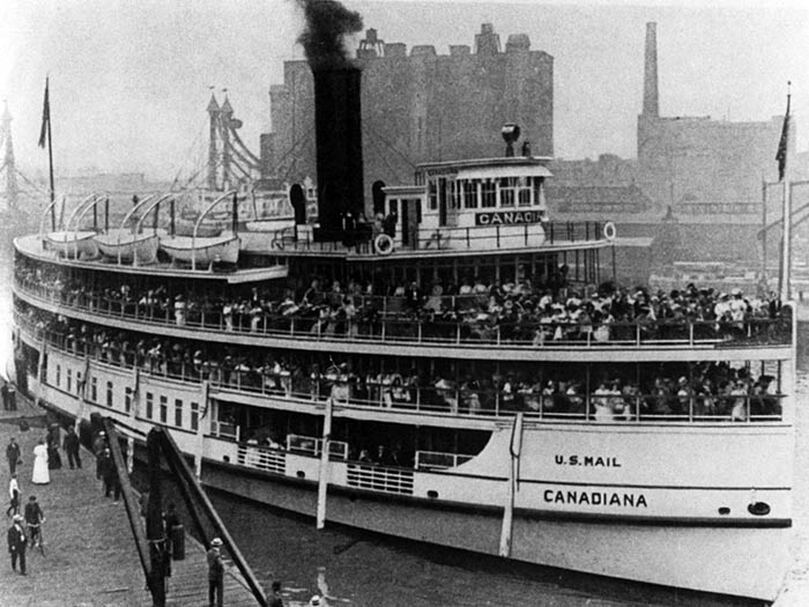

Opened in 1984, with funding from the Packard family of Hewlett-Packard fame, the non-profit aquarium is located in a reconstructed and redesigned sardine canning factory that has earned architectural awards. Some of the equipment from that time is included in a display along with tanks of fish. The aquarium is renowned for its laser focus on the regional marine ecosystem and its research and ocean conservation projects have influenced the field, including helping to designate Monterey Bay a federally protected marine sanctuary. Their Seafood Watch program helps consumers make sustainable choices when they are shopping or out to dine. The “irony” of the aquarium’s location in the same building that played a significant role in overfishing has been noted since its inception. But I’d choose a different word: Hope. The ferry to Crystal Beach docked in Buffalo, NY, 1910. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Canadiana White fear ends an era My family has a long history with Crystal Beach, which is located on the Canadian shore just across Lake Erie from Buffalo. In the 1950s, both my parents rented cottages at Crystal Beach with their friends, although they didn’t know one another then. And, every summer, they took me and my sister and an assortment of cousins to the amusement park, where we rode apathetic ponies, ate soft pretzels and cinnamon suckers, and screamed on the Comet roller coaster (full disclosure: I was too chicken ever to get on it). See more images at: https://wnyheritagepress.com/content/crystal_beach_-_1900-1922/index.htm I heard stories about my maternal grandparents taking the Canadiana, a ferry between Buffalo and Crystal Beach that began operations in 1910, to go dancing. The Crystal Ballroom opened in 1925 and at the time was the largest dance hall in North America, with room for 3,000 dancers, and famous big bands played to sold-out crowds. To me, it sounded old-fashioned and incredibly romantic. But the ferry had ceased operations even when my parents were young, and I remember hearing that it had somehow become “dangerous.” I never questioned what exactly that meant. On Memorial Day in 1956, a “riot” on the Canadiana made national news. On the opening day of the summer season, Buffalo teens swarmed to the park, wearing club jackets that marked their neighborhood, ethnicity, and race. There were rumors of gang fights. Shortly after the ferry docked, some white servicemen taunted a group of Black teenagers with racial slurs. A young Black man pushed a white soldier into the lake. Hostilities between Blacks and whites increased throughout the day as news of the incidents spread, along with a rumor that a Black girl had been harassed by white men. Eventually, fights broke out, leading to some injuries that brought in the Canadian police. They arrested five young Black men and four Italian-American white men—all with switchblades and knives. When the news spread, Black visitors began to protest the arrests and some white men attacked a Black family. The police blamed whites for the racially motivated violence. Ferry managers heard about the fighting, and in the evening, as people boarded the Canadiana to return to Buffalo, young men were searched for weapons. On the boat, the teens segregated themselves by race and age. Rival Black gangs began fighting, and others ran around the upper deck setting off firecrackers. Then a group of Black girls began to taunt some white girls and pull their hair. Rain made everyone crowd below the decks and passengers of both races felt trapped and frightened. Buffalo, New York, police and an anxious crowd await May 30, 1956, on its return from the Crystal Beach Crystal Beach. Courier-Express, May- 31, 1956. Courtesy Buffalo State Express Collection and Buffalo and Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society. Buffalo police met the boat at the dock and arrested three young Black men who had been detained by crewmen. They escorted thirty terrified white girls to the precinct house, where their parents picked them up. Five people were treated for minor injuries. It could hardly be called a riot—there were no deaths, little property damage, and few injuries. But to white people in search of relaxation and recreation, the presence of Black people swimming, dancing, and enjoying their historically mostly-all-white park had triggered fears of interracial mixing.

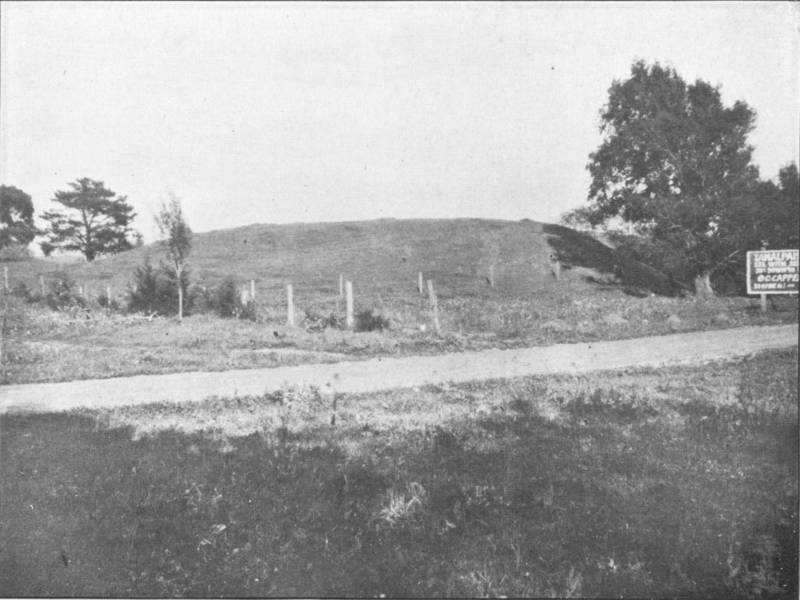

In the aftermath, two local journalists wrote about the white passengers’ overwhelming fear and hysteria, and newspapers all over the country picked up the story, despite many more moderate voices who blamed the incidents on “juvenile delinquents” of both races. Only two years after Brown vs. Board of Education, Southern newspapers used the incident to argue that integration could not succeed. The ”riot” reflected the turmoil of a city undergoing rapid integration as Black migrants moved North after World War II and attempted to enjoy the benefits of life outside the segregated South. Before then, there were so few Blacks there was no need to segregate recreational places like Crystal Beach—local Blacks understood that it was reserved for whites by custom, if not law. The riot drastically reduced ridership on the Canadiana, and integration of the park eventually led to its long, slow decline, a process mirrored in other cities and parks. The Crystal Beach amusement park closed for good in 1989. Just a year before my college graduation, I barely noticed. Now the site that served as a beloved place of recreation for countless families for 101 years is a gated community called the Crystal Beach Tennis and Yacht Club. They’ve succeeded in re-segregating it—this time by class. Note: The ferry to Crystal Beach must have been revived for a brief time in the early ‘80s, when I took it with a friend, but I haven’t been able to find any reference to that period. That's what history's all about My sister and nephew visited me and my husband recently here in Half Moon Bay, California. In the photo, we are standing in front of an old-growth redwood tree named Methuselah that’s over 1,800 years old. Ancient things in nature always make me imagine what changes they have seen over the vast span of their lives. Born in 217 AD, the Methuselah tree was already a couple of hundred years old when the Roman empire fell. From its vantage point on a high ridge of the Santa Cruz mountains, it saw the first Europeans sail by in 1542, when they missed the entrance to San Francisco Bay because of the fog. At that time, the area had been densely populated for tens of thousands of years with indigenous groups engaged in active trade networks. Shellmounds created by these groups used to dot the landscape—and bay-scape. Layers of soil, shell, and rock, sometimes 30 feet high, served as burial sites, meeting places, and focal points for navigating the bay. Countless generations watched them rise. Now, they have mostly disappeared. In 1909, archaeologist Nels Nelson documented over 400 mounds although there had once likely been many more. They were quickly being destroyed—in one case, to make way for a paint factory. A shellmound in Mill Valley, as photographed by archaeologist Nels Nelson in 1909, from Nelson's report “Shellmounds of the San Francisco Bay Region.” Read more. This past winter, relentlessly violent storms changed the landscape around where I live. Cliffs along the beach eroded, dropping huge chunks of earth covered with ice plants and birds’ nests into the ocean. Trails and bridges were washed out. Trees were downed everywhere. There were mud slides in the burn scars from the destructive wildfires of 2020. The blackened skeletons of burned trees still disturb me despite green carpets of new growth beneath them.

Seeing the area for the first time, my visiting sister and nephew didn’t see the changes that sadden me. They only saw spectacular beauty. It made me realize that different is disturbing primarily because it is unfamiliar and so generates worry and fear in some of us (and excitement in the people I envy). But we should remember that we do that to ourselves. Difference and change are not inherently bad. In fact, nothing is certain in life except change. The certainty that things will certainly change has comforted me during hard times and weighed me down in good times. History is the deliberate study of change. Perhaps it can help us to become familiar with the inevitability of change in a way that helps us to appreciate the constant change going on around us. Take a moment to look around at your familiar environment—imagine what it once was like, how it is now, and what it might become. Make friends with history, make friends with change. |

AuthorHeidi Hackford explores how past and present intersect. Archives

November 2023

Categories |