|

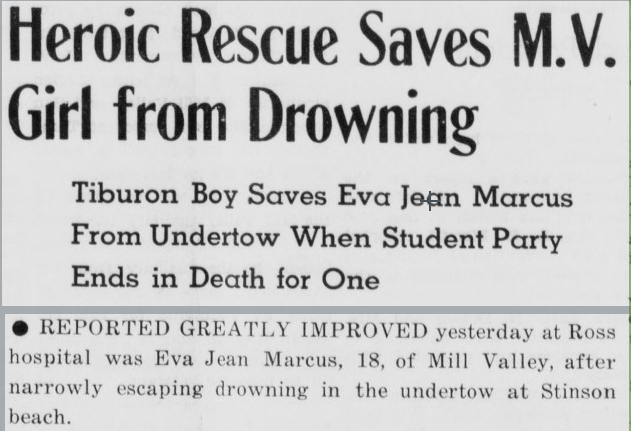

Warren, Sara, and Marshall Plamondon, 1935 When research proves you wrong One of the things that I love about studying history is the thrill of uncovering a new fact or story. It’s even more satisfying if the new fact or story confirms your own theory or hypothesis. The flip side is that sometimes you are proven wrong. That can range from being merely disappointing to deeply disturbing, depending on the stakes. I’ve always wondered how many graduate students writing dissertations or academics researching books have quietly ignored evidence that disproves their thesis. We’re only human, right? In writing this blog about a real-life hero, I discovered that the thesis that prompted my research was probably wrong. It all started with a conversation with my stepkids (see “Origin Stories” below) that made me wonder to what degree a family member’s behavior can affect a descendant’s behavior. The study of epigenetics even shows that an individual’s lived experience can influence the behavior of their genes. I’ve been told by various family members that my father-in-law, Jim (who is now 91 years old), despite living close to the Pacific Ocean for his entire life, never went to the beach and doesn’t like to swim. I thought this was odd, especially since he had served in the Navy. But after that Thanksgiving conversation, I remembered that I had also heard that Jim had an uncle who died young while rescuing someone from drowning. Ah ha! I thought—Jim’s aversion to the beach and swimming was perhaps instilled in him by traumatized family members when he was a child. I set out to learn more about the circumstances of the tragedy. Thanks to the California Digital Newspaper Collection, which provides searchable records of a huge swath of small local papers, I was able to gather not only the facts around that event but something of a profile of Marshall Plamondon—the younger brother of Jim’s mother. Marshall and his twin brother Warren were born on September 13, 1919, just north of San Francisco, and attended Mt. Tamalpais high school. As a blue-eyed, brown-haired freshman, Marshall was 5’6” tall and 132 pounds. Football was his favorite sport, but he also ran track and played basketball and baseball. He had met a girl he liked. Eager to travel, he aspired to attend Annapolis and become a naval officer. Marshall went on to become a star athlete and class president and make the dean’s list with four As. After graduation, he did not go to Annapolis but instead to nearby Marin Junior College, where he continued his student career as a sports star and class president. Mill Valley Record, May 14, 1940 On May 9, 1940, when Marshall was 20, he and a group of students went to Stinson Beach after classes. While he was walking in the water with Eva Jean Marcus and Donald Ballard, all three were caught by an undertow and pulled away from the beach. Apparently, Marshall helped Eva stay afloat until, exhausted, he passed her off to Ballard and disappeared under the waves. Ballard and Eva eventually made it back to the beach but were unconscious and had to be resuscitated. Marshall’s body was never found. A year later, a memorial bench was placed in his honor on the college campus. Eva Jean, a Mill Valley socialite, went on to marry a lieutenant-commander in the Navy who had survived Pearl Harbor. They had at least two children and Eva died at the age of 73 and her husband at 92. Donald Ballard went to UC Berkeley, moved to Eureka, where he worked at a bank, and was married in 1931.

The tragedy happened only three weeks after Marshall’s father had died of heart failure and three days before my father-in-law Jim’s 8th birthday. Jim’s mother, Sara, was six years older than her twin brothers and had helped raise them—she once told Jim, that she felt responsible for them, more like a mother than a sister. She had also adored her father. Four years after Marshall drowned, the youngest brother, who became a Marine, was killed in the Pacific during WWII. This was enough to traumatize anyone, I thought, and certainly enough for Sara, a young mother still in her 20s, to pass along a dread of loss in the form of an aversion to the beach and swimming to Jim. Then my theory began to fall apart—even if I had conveniently forgotten Jim’s time in the Navy. Jim recently wrote a memoir for the family. In it, he notes that his mother suffered from ulcers (evidence of stress from trauma? I wondered, still hanging on to my theory) and began to have epileptic seizures in her early 30s that restricted her activities (it’s getting harder to hold on to my theory at this point). Jim wrote that his father was a rather cold man, a hard worker, who didn’t believe in vacations and rarely spent time with Jim (my theory is fading fast). Finally, a few pages later, I read that Jim did in fact go to the beach when he was in college. And, I belatedly recalled that he had been happy to attend our wedding on Pescadero Beach. Quite disappointed (I hope to reach the point soon where I’m glad that my lovely father-in-law avoided a lifetime of trauma!), I let go of my theory.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHeidi Hackford explores how past and present intersect. Archives

November 2023

Categories |