|

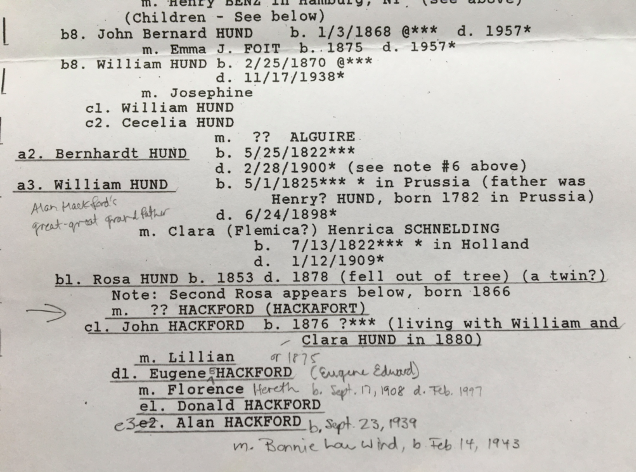

Missing Names, Missing History Visiting my parents recently, I came across an envelope with a few documents and photos related to my father’s family history. Someone had done some genealogical research. There was a family tree that went back five generations, and I discovered a bit of a mystery. The entry for my dad’s paternal great-grandfather read: “?? HACKFORD (HACKAFORT).” The first name was missing and there was apparently some confusion about his last name. Next to him was the name of his wife, Rosa Hund, and the chilling note: “Fell out of tree.” Rosa had apparently died at the age of twenty-five, leaving a two-year-old-son named John (my father’s grandfather). The boy was noted as living with his Hund grandparents in 1880 when he was four years old, that fact perhaps gleaned from a census record. This suggested to me that John’s father had left him to be raised by his dead wife’s parents and had moved on, perhaps never to return since his first name had been forgotten. The child, John, carried the last name “Hackford” forward, however. I had been told the family Anglicized the name from “Hackfort” to “Hackford” during World War I, when German-Americans were eager to dissociate themselves from a country with which the US was at war, but the genealogy suggested that perhaps the name may have been changed earlier. Did someone remember that the mystery father had once said his last name had been changed? Or, did the family researcher discover that the name had once been Hackafort, and if so, why hadn’t that person been able to also discover the missing first name. It’s a frustrating puzzle.

Our names are fundamental to our identity. From the time we’re born until we die, our names tell us where we belong in the world and are a crucial factor in determining our sense of self. As anyone researching history will tell you, a missing name is more than just a gap in the record—it is a mystery to be solved, a hole of possibility that encompasses all things until we can fill it with information. Women’s first names and maiden names can be lost to history since often the sole record of their existence is a cemetery headstone identifying them only as “wife of”. The journal of 18th century mid-wife Martha Ballard, for example, is extremely unusual in that she not only kept a journal but also that she recorded her full name. Enslaved people were often not permitted to retain their birth names and may have been given new surnames or even first names when they were sold—making tracing ancestry very difficult. Similarly, when immigrants could not make themselves understood by immigration officers, those officials recorded what they thought they heard. That also happened when settlers encountered Native-American names. Who knows how far removed they are from the originals? We are a country of immigrants, and we may find unfamiliar names difficult to pronounce or to remember. In my late twenties, I discovered with horror that I had been pronouncing a good friend’s name wrong since I met him the first week of college. Many immigrants change or shorten their names so that they more closely resemble typical American names—losing some part of themselves to make it easy for the rest of us. Please, let’s make a sincere effort to learn people’s true given names and how to pronounce them properly. It might remind us all that we’re not strangers but fellow travelers on the same human journey.

0 Comments

Mission San Francisco de Solano, Sonoma, CA. Time To Retire It Ever since I was a kid, I’ve loved the idea of the Old West. My parents read the Little House on the Prairie books to me and my sister, and we never missed the TV show starring Michael Landon of Bonanza fame. We had a large collection of Best of the West action figure dolls and an assortment of horses and even a covered wagon. Our plastic pioneers trekked across a sand-colored carpet remnant in the basement and constructed towns centered around the two-foot-high general store and log cabin that my parents made us for Christmas. I secretly regretted that my immigrant ancestors never got any farther west than the western edge of New York State. Amy and Heidi Hackford playing “West” in the mid ‘70s. When I could read myself, I devoured Louis L’Amour novels and even wrote my own (terrible) Western stories. I had a crush on Shane and other gunslingers. As I grew up, I read Lonesome Dove and enjoyed John Wayne movies and Clint Eastwood spaghetti Westerns, and I went to theaters to see Tombstone and 319 to Yuma. Now I live on the edge of the Pacific Ocean in California—it’s as far West as I can go in the US. And I love that my husband’s family springs from pioneers who arrived here in the 1850s. Recently, we went wine tasting in Sonoma County and stopped at the quaint town square. On one side of the square is a state historic site, the restored Mission San Francisco de Solano. It is the last in the line of Catholic mission established throughout California. Founded in 1823, it was the culmination of three hundred years of Spanish settlement. Signage at Mission San Francisco de Solano. My husband and I were startled by text of the signage, which told the “heroic” story of General Vallejo, tasked with establishing a town near the mission and defending it. Native Americans built the military barracks across the street from the mission church as well as a mansion where the general lived. They did so, according to the sign, under the general’s “leadership,” and they also “did everything from caring for his many children to grooming his horses.”

So, after the Spanish had wiped out most of their population with disease, aggressively tried to eradicate their culture and convert them to Christianity, and forcibly enslaved them, these Native Americans had the privilege to work at “one of the finest homes in California.” Apparently, the upcoming 200-year anniversary of the mission has prompted a re-examination of its history. It will no longer be termed a “commemoration” and plans are currently underway to update the historic interpretation at the site. There is, of course, a dark side to our cultural depictions of the Old West. Like the mission story, it glorifies land grabbing, genocide, oppression, and gun violence. And the roots of that history are deep. Recently, my bucolic beach town of Half Moon Bay made the national news. Only a week after massive winter storms had devastated the area, a local farmworker shot and killed seven of his coworkers with a legally purchased handgun. Investigations have revealed that the workers lived in substandard conditions typical of the country’s underclass, paid well below the minimum wage and living in shipping containers without running water or electricity. Is this how Old West culture manifests today? Maybe it’s time for a change. The Keeneland Library, Courier Journal via Imagn Content Services, LLC. See story When stereotypes undermine skills Horse racing was insanely popular in the antebellum South, and those who could afford thoroughbred horses and ride them well garnered respect and enjoyed high status. Thomas Jefferson took pride in his purebred horses and in his reputation as a superior horseman. Men like him paid close attention to bloodlines and breeding, which perhaps fed their obsession with doing the same for their enslaved workers. They believed, for example, that people from different African nations had different traits that made them better workers or more prone to running away. Geraldine Brooks’ latest novel, Horse, (see below) is based on the true story of a Black horse trainer who raised champions in Kentucky, the heart of Southern horse racing, before the Civil War. It’s part of a larger story that many may not know—that enslaved people could be found working outside the cotton fields in a wide range of professions and sometimes attaining a high degree of skill. Thomas Jefferson relied on his enslaved carpenter, John Hemings, to undertake the most intricate woodworking at Monticello. Richmond and other Southern urban centers were full of enslaved skilled and industrial workers, whose masters had rented them out to factories, mills, dockyards, and artisans’ workshops. But Horse brought to my mind another image—the lawn jockey. These statues of Black jockeys, popularized in the 1950s stood a few feet high, and were often placed beside a driveway or a front gate. The figures usually held a hitching ring or a lantern, suggesting they were there to tie up a visitor’s horse or light their way to the house. I’m pretty sure I saw a few in my Northern suburban childhood in the 1970s. Lawn Jockey from South Carolina. Library of Congress Grace Elizabeth Hale’s Making Whiteness, argues that caricatured depictions of Black people like the lawn jockeys, as well as stereotyped images used in advertising (think Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben) and entertainment (Amos and Andy) were first introduced in the late nineteenth century. Representations of Blacks that emphasized servility, foolishness, and stupidity united post-Civil War Whites from North and South in a shared consumer culture that excluded Blacks.  Display of racist Obama paraphernalia at the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University. You can explore the exhibit virtually here. These representations attempted to deny the reality that Black workers were present in and capable of mastering all kinds of skills and professions, even under conditions of slavery. When Whites could no longer gain from renting or selling skilled slaves, they demeaned and undermined Black people, perhaps in a bid to reduce the competition in a free labor society.

I wonder if a growing trend in higher education might help rectify the inequities resulting from these historic conditions. It involves moving away from expensive four-year college degrees—that often offer only questionable advantages for a prospective employer—toward certificate programs, many online, that demonstrate mastery of concrete and specific skills. Let’s hope the outcome is better for underserved people. Catholics in the cities

As a lapsed Catholic, one of the few times I think about the faith I was raised in is during the holidays. Catholic churches and schools were a critical part of the lives of my ancestors on both sides of family, their influence gradually dwindling from my grandparents, through my parents, and to me as they moved away from their heavily German-American parish in Buffalo, New York, to the suburbs. Their experience was not unique. John T. McGreevy’s Parish Boundaries: The Catholic Encounter with Race in the Twentieth-Century Urban North (1993) makes the case that racial unrest in many inner cities was essentially a clash between Black migrants from the South and Catholic communities that had been established by waves of immigrants. Throughout the first four decades of the 20th century, Catholic churches were established throughout northern cities and clergy encouraged parishioners to invest in their neighborhoods. Catholics gave money to build not only churches, but also rectories where priests lived, convents to house nuns, parochial schools, and hospitals. Catholics identified themselves by their parish and participated in social activities, clubs, and sports centered around the church, not to mention mass on Sundays. When a prominent Catholic monseigneur died in Buffalo in 1941, 30,000 people filed past the body. Our Lady of Victory parish in Lackawanna, an industrial suburb near Buffalo, was the city’s second largest employer after Bethlehem Steel. Parishes were often organized by nationality, separating immigrant groups into German, Irish, Italian, and Polish neighborhoods, and even those for Black people in the earlier years of the 20th century, although Black Americans often objected to being segregated. Catholics were encouraged to buy their own homes in the parish, ensuring stability and funding for parish institutions, like local Catholic schools. However, as McGreevey notes, as second and third generation Americans from immigrant groups began to prosper, especially in the post-WWIII years, many moved to the suburbs, leaving room for opportunistic real estate agents to scare those left behind into selling their property cheaply by stoking fears about Black people moving in. This “block busting” practice allowed them to profit by reselling to Black buyers at higher prices, saddling them with large mortgages. Those who couldn’t afford to buy, or were denied mortgages through red lining practices—where banks refused mortgages to qualified Black applicants in certain neighborhoods—had to rent from landlords who may not have been motivated to maintain the properties, resulting in slums. Some Blacks were herded into public housing projects built by federal and local officials in heavily Catholic neighborhoods. White Catholics, including parish priests, frequently resisted integration of their neighborhoods. In the heart of the heavily Irish South Buffalo, two prominent priests led rallies to protest a proposed housing project. Monsignor John Nash of Holy Family Church said: “The Okell Street project threatens to destroy the work of 40 years to build up the South Park district. The right to protect our homes is as sacred as the right to defend our lives.” (pg. 73) White Catholic mobs threatened Black neighbors and beat them, set fire to their houses, and threw bricks through windows. Even Black Catholics were treated with daily disdain—spit upon, called names. At Mass, White churchgoers would often vacate a pew if a Black person sat down beside them. White Catholics defended their actions by arguing that no one cared about working-class people who were watching their home values—their only insurance against old age—rapidly decline. But they blamed their Black working-class neighbors for the decline rather than the true culprits: opportunistic (White) real estate agents, (White) slumlords, and (White) politicians. Ironically, throughout this time, the Catholic leadership, all the way up to the Pope, was moving toward promoting racial tolerance and inclusion as key Catholic tenets. Liberal Catholics worked for interracial harmony and priests and nuns joined freedom marches and protests during the Civil Rights era. But they ultimately failed to instill the message in laypeople. White Catholics fled the inner cities, leaving deteriorating homes, schools, and churches for Black Americans to resurrect. Some succeeded, many did not. So, who exactly was to blame for the decline of our inner cities? Main image: Sisters of Charity Hospital was the first hospital in the city of Buffalo. It was founded in 1848 by John Timon, the first Catholic Bishop of Buffalo. https://buffaloah.com/a/stlou/14/sisters.html Student loan forgiveness as racial justice

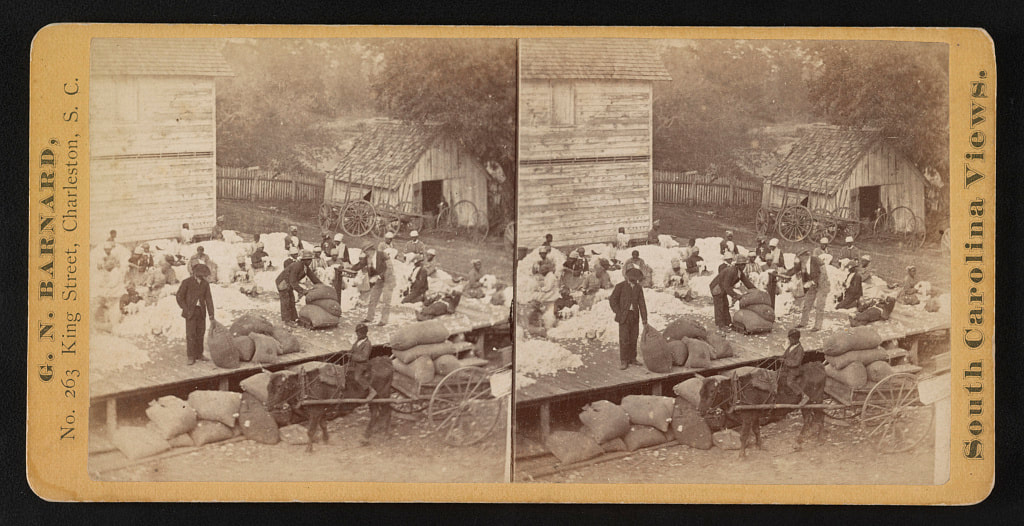

President Biden recently announced a new plan to forgive $10,000 of federal student loan debt for each borrower. For those concerned about the disproportionate share of debt held by people of color, particularly Black women, who owe the most, this was welcome news and a matter of racial justice. Black students have less generational wealth to draw on than White students to pay the bills for higher education. Criticisms of the debt forgiveness plan are many, but some seem strikingly familiar. That it’s too expensive, an example of big government overreach, and will encourage people to be lazy were arguments used 150 years ago by President Andrew Johnson when he rejected plans to aid the newly emancipated slaves. Historian Eric Foner’s classic work, A Short History of Reconstruction (1990), delves deeply into the time immediately following the Civil War, when many of the conditions that created today’s wealth gap were formed. It’s a complicated story, but by the time Reconstruction ended in 1877, Black people’s status as an underclass had been firmly established. When the Civil War ended, emancipated slaves and many Union supporters believed that it was only fair they should receive portions of the land they had labored on, unpaid, for generations. Congress authorized the Freedmen’s Bureau to divide abandoned and confiscated Southern lands into 40-acre plots. This redistribution would have weakened the power of the plantation class and provided the former slaves with a means to earn their own livings. However, Johnson ensured it never happened. In areas where the process had already begun, Black families were displaced and the land was returned to its former owners. Former Confederates worked to restore as much of the slave system as they could. Many Northerners, even those who advocated for the freedmen, assumed the easiest way to restore the South’s economy and transition to a system of free labor was to keep the ex-slaves on the plantations but pay them wages. To ensure that this would happen, Whites refused to rent or sell land to Blacks. In urban areas, only low-wage menial labor was available and Black families were segregated into squalid shantytowns. States passed Black Codes that required ex-slaves to sign restrictive labor contracts with severe punishments for breaking them, including involuntary plantation labor. Apprenticeship laws required black minors to work for planters without pay. Men, women, and children were whipped, beaten, and hung for “insolence” or “insubordination” as defined by the Codes and interpreted by Whites. Black homes and communities were burned and destroyed. Foner says: “Freedmen were assaulted and murdered for attempting to leave plantations, disputing contract settlements, not laboring in the manner desired by their employers, attempting to buy or rent land, and resisting whippings. . . . Charges of “indolence” were often directed not against blacks unwilling to work, but at those who preferred to labor for themselves.” (pgs. 53, 60) Whites also joined together to fix wages at low rates, evicted Black laborers without pay, and refused to give ex-slaves their share of the crop. The freedmen had no recourse with all-White police and judicial systems. They were barred from receiving poor relief and using parks and schools, despite paying taxes to support public services. Yet, despite the perpetual threat of violence and the difficulties of meeting their basic needs under these conditions, emancipated slaves spent their hard-earned money and limited time avidly pursuing education. Outlawed during slavery (90% of Blacks were illiterate when the Civil War began), education was seen as central to the meaning of freedom. Children and adults flocked to the schools set up in churches, basements, warehouses, and homes. In New Orleans and Savannah, emancipated slaves studied on the sites of former slave markets. Forgiving student debt is the least we can do. Image: Laborers, including ex-slaves, preparing cotton for gins, on Alexander Knox's plantation, Mount Pleasant, near Charleston, S.C. during Reconstruction [1874]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Marketing the past as a commodity My husband Eric and I just returned from a trip to Norway, where we did some sightseeing in two coastal cities, Stavanger and Oslo. It’s a beautiful country, with rolling hills, forests, and deep blue fjords. Oslo dates to the year 1050, Stavanger to 1125. Viking Cruises, a $1.5 billion company, was founded by a Norwegian, and its logo is a Viking ship, evoking seafaring ancestors. Not only Viking, but other cruise ships were ubiquitous in the harbors of the two cities. Massive even by modern standards, the fifteen story floating hotels always scored the most scenic sections of the harbor, butting up against historic sites in both locations.  Cruise ships at historic sites in Oslo and Stavanger, Norway. In Oslo, the docked cruise ships blocked the view of the harbor from the 800-year-old Akershus Fortress on the hill above the city. From the harbor itself, as we found during a boat tour, the fortress was completely obscured. In Stavanger, the ships obstructed the views from the 18th century wooden houses constructed on the site of the “gamle,” or “ancient,” part of the city. Views and access to history were reserved for those who could pay . . . a lot.

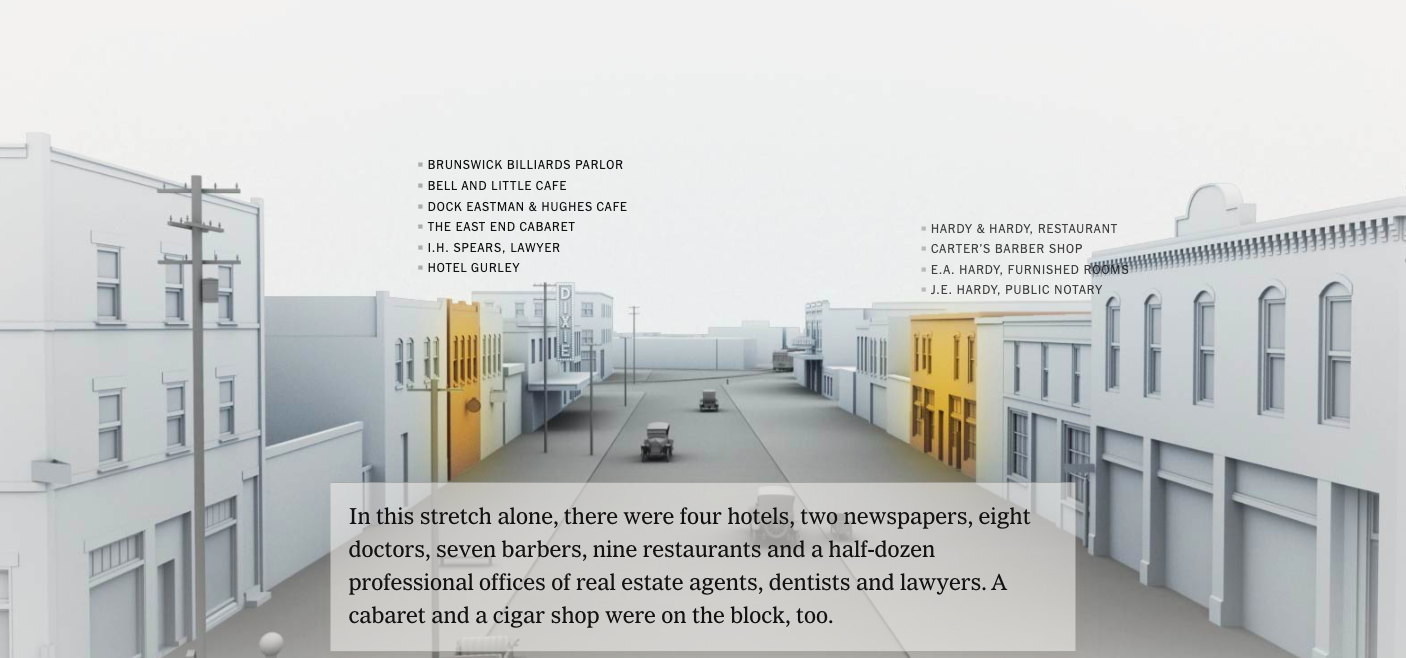

Prices for a cruise range in the thousands. Marketing conveys to passengers that they are adventurous explorers who will discover foreign peoples and cultures. On Viking, the all-inclusive menu includes “one complimentary shore excursion in every port of call” and “Enrichment lectures and Destination performances” sandwiched between free Wi-Fi and access to the Nordic Spa and state-of-the-art fitness center. History and culture have become just another commodity to be consumed along with the buffet dinners and 24-hour specialty coffees and teas. Cruise ships often stay in port only one night, so those who want to disembark have only a few hours to take guided tours that inevitably end near stores selling souvenirs that play on cultural stereotypes and offer cultural icons reduced to refrigerator magnets. Presumably, this represents the economic benefits to the host cities, along with some docking fees. While passengers are consuming the local history, many of the ships themselves embody some of the worst of modern humanity’s consumption excess. Port communities and animal life endure air, light, and noise pollution. Cruise ships are legally permitted to dump food waste and treated sewage into the ocean, amounting to a billion gallons a year (see article). One cruise ship produces roughly the same amount of carbon emissions as 12,000 cars. The “bunker fuel” cruise ships use puts out black carbon, sulfates, and other chemical pollutants. Black carbon is the second leading cause of global warming after carbon dioxide (read more). There are some cruise lines that are taking steps to become more eco-friendly, such as installing solar panels and exhaust scrubbers, using water more efficiently, recycling, converting waste to energy, and other measures. As we consume our history, whether it’s on cruise ships or flying or driving to historic sites, we should be mindful of the tradeoffs and seek out—and be willing to pay for—cleaner options. Or there just might not be a future generation to discover how we live today. Finding Black people and places in history Recently, I learned that there used to be a thriving 19th century village just a couple of miles down the road. There’s nothing left of Purissima now but a cemetery and a cypress grove. When the railroad left, the town died. Reading about this “lost” village reminded me of the vanished Vinegar Hill, near where I lived in Charlottesville, Virginia (see image above). Vinegar Hill was a thriving Black community razed in 1965. The city’s largest Black neighborhood and a hub of social life, 139 homes and 30 Black-owned businesses and a church were destroyed in the name of “urban renewal.” The land was valuable, and the city was eager to redevelop it into shops and apartments . . . for White people. This kind of destruction was the rule more than the exception in the rapidly growing post-WWII United States. In the last few years, some cities have explored efforts to compensate residents and their descendants for property taken by eminent domain for public projects (read more). In my hometown of Buffalo, NY, I often traveled on the Kensington Expressway, passing large and stately homes butting up to the traffic. Recently called a “mistake” by NY’s former governor, the road destroyed the thriving Black communities around Humboldt Parkway—part of the beautiful park system designed for the city by Frederick Law Olmstead. Humboldt Parkway, yesterday and today. Of course, Black communities were also lost through violence and destruction. Suppressed in the papers of the time but later referred to as a “race riot,” what happened in Oklahoma 100 years ago has been more accurately renamed “the Tulsa race massacre.” Following an incident between a White woman and young Black man in an elevator (it is believed he may have stepped on her shoe), White vigilantes burned more than 1,200 homes and killed hundreds. Claiming they feared that word of the young man’s arrest would draw unruly Blacks from the surrounding country and nearby neighborhoods, they preemptively annihilated what was known as “the Black Wall Street.” You can walk through the recreated lost community in this interactive NYT article. The narrative used in Tulsa was honed during slavery. In Tumult and Silence at Second Creek (1995), historian Winthrop D. Jordan, explores a slave conspiracy in Mississippi in 1861. Hearing of the outbreak of the Civil War, a number of slaves in a wealthy, established plantation community allegedly plotted to kill their masters and take the White women. Fearing the unrest would spread, dozens of slaves were questioned and summarily executed by an extra-legal “Examination Committee” of slave owners. These slaveowners gave up their legal right to be compensated for their executed slaves in the name of secrecy, fearing that it might inspire other uprisings or provide ammunition to the Northern cause. One woman wrote to her niece: “It is kept very still, not to be in the papers . . . don’t speak of it only cautiously.” Although the houses where the Second Creek slaves lived have long disappeared, many of the mansions still stand. Some are tourist attractions.

***To see what communities have been lost in your hometown, google “urban renewal Black neighborhoods [YOUR CITY].” Main image: Vinegar Hill in the 1930s. Read the story. Why we need memories along with statisticsI’m currently reading a biography of Franklin Roosevelt by H.W. Brands. I was curious about how the US dealt with the national traumas of war, pandemic, and depression that occurred throughout his lifetime and the lifetimes of my grandparents. Because, at some point in the last year or so, I’ve become a bit desensitized to the human suffering from covid, the war in Ukraine, and food and housing insecurity.

Apparently, this is a normal psychological response, the brain adapting to on-going horrors so we can continue to function. So, it is makes sense that it’s hard to fully comprehend the human cost of numbers like these: in 1931, 100,000 gainfully employed people—most of them the sole breadwinners for their families—lost their jobs every week . . . and every week after that, for another 130 weeks just in the first four years of the 10-year Great Depression. Harry Hopkins, who ran the New Deals’ Works Progress Administration, noted, “You can pity six men, but you can’t keep stirred up over six million.” He sent reporter Lorena Hickock to gather human stories behind the statistics. In one case, after an interview in a chilly North Dakota farmhouse, she went out to her car to find it full of farmers who had crawled inside to keep warm. One New Deal program, the Federal Writers’ Project, sent thousands of unemployed journalists, novelists(!), and poets to collect people’s memories in oral histories, including those of ex-slaves. I’ve used them for various research projects, and invariably the interviewees are surprised that anyone would want to hear stories from ordinary people. This attitude echoed my grandparents, who responded to my questions about their Depression experiences by saying, “Oh, you don’t want to hear about that old stuff.” But I did, indeed, want to know why my maternal grandmother used old nylon stockings to tie things up with “because of the Depression.” She told me once that, “The Depression was having a nickel and not knowing when or where you would get the next one if you spent it.” My maternal grandfather worked any job he could find, often lucky to be selected from among hundreds because he was tall and stood out in the crowd. My paternal grandfather retained his job, and my grandmother said the Depression affected them only in that some things were hard to get, like sugar. When she died, we found bags of sugar she’d hoarded in the back of a cupboard. (After the pandemic, I will always have a six-month supply of toilet paper.) The written word isn’t the only way we can retain stories. The Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial was a novel way to commemorate service in war when it was dedicated in 1982. Rather than a statue of a famous general, the names of the over 58,000 soldiers who fought are listed on the Wall. It’s a visceral representation of real people who each had their own stories. Similarly, in July 2021, 600,000 white flags were planted on the National Mall to draw attention to those lost to covid. These visual cues certainly help to represent people better than an aggregate number, but we must continue to gather the stories of ordinary people, including all of us, who are experiencing our national traumas. Only then can those memories become a part of history, a reminder of our shared humanity and a reminder that there are always real people and real lives behind the numbers. Sources H.W. Brands, Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (New York: Anchor Books, 2008), 420, 422. David Kennedy, Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 167-168. The Art of Parenting a Democratic Republic

The January 6 congressional hearings started last week, exposing the details of a coup attempt to subvert the peaceful transfer of presidential power for the first time in US history. The Founding Father’s would have been appalled. And, George Washington, the only president who could ever credibly claim that a majority of the people would have been happy to have him rule for life, would have been the most disgusted of all. Like any good parent, Washington fostered and protected the republic in its youth until the systems and habits of a nation could take root. He worked to establish a strong central government and to unify the states beneath it. This was an unprecedented task in the late 18th century, and it was not an easy one. It’s a bit of a contradiction to unite states that fought a war for sovereignty. Joseph Ellis’ Pulitzer Prize-winning book Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation (2000) argues that the divides we see throughout American history were there from the beginning and are unlikely ever to heal. Though the Founding Fathers were all white, privileged, males, they did not agree about the fundamental basis of the nation, and “in a very real sense we are, politically, if not genetically, still living their legacy.” Individual liberty is the core belief of small “r” “republicanism,” articulated best by Thomas Jefferson. It is libertarian and at its most extreme anarchic. By contrast, the “Federal” viewpoint, embodied in Alexander Hamilton, promoted surrendering individual interests to the larger collective. At its worst, it has despotic implications. To a degree, these differences became institutionalized in the party system. Although Washington was a Federalist, his public standing was so high that he was essentially a republican king. Described as “the Father of the Country” since 1776, Washington was regal in stature with a martial dignity and charisma that commanded attention. His image was everywhere—on paintings, prints, coins, silverware, plates, and household tchotchkes. The capitol city was named for him. He rode a white stallion with a leopard cloth and a gold-trimmed saddle. He accepted laurel crowns at celebrations that resembled coronations. With the force of his reputation and personality, Washington held the new nation together. Ellis writes: “He was living the great paradox of the early American republic: What was politically essential for the survival of the infant nation was ideologically at odds with what it claimed to stand for. He fulfilled his obligations as a ‘singular character’ so capably that he seemed to defy the republican tradition itself. He had come to embody national authority so successfully that every attack on the government’s policies seemed to be an attack on him.” Washington was offered concrete opportunities to become a real king, but at every turn he declined. He refused to take part when disgruntled army officers tried to recruit him to the insurrectionary Newburgh Conspiracy, and the plot fizzled. He resigned as commander of the Continental Army in 1783 without drama. In September 1789, Washington published his “farewell address” in the newspapers to inform the people he served that he intended to retire when his second term ended. Rejecting his own cult of personality, he signaled for the last time that he had no intention of ruling until the end of his life or appointing a successor. Like a good parent, he stepped aside to let the nation continue to grow up, trusting (and hoping) that the principles he had instilled would lead it down the right course. From the beginning, the peaceful transfer of power in this country has been dependent on the good behavior of the president rather than codifed in law. It probably seemed unnecessary to do so with Washington in office. But, as we have seen, that can be dangerous. We must be vigilant to protect our democracy, and we must not take it for granted. Watch the January 6 hearings. Image credit: The Washington Family by Edward Savage in the Andrew W. Mellon Collection at the National Gallery of Art The problem with house museums

Montpelier blew it. In a discussion with my museum colleagues the other day, we explored the recent unfortunate events at the historic home of James Madison in Orange, Virginia. A colleague from my days at Monticello was fired, along with other staff, after the board refused to honor their commitment to implement board parity with descendants of Madison’s slaves. Although they received praise and a lot of positive press when the move to include slave descendants on the board was announced last year, and despite the pleas of staff and a petition signed by 11,000 people, the board reneged. In a rare move, the National Trust, which owns the property, stepped in to insist that the members nominated by the descendants committee be seated immediately. One of my colleagues noted that historic homes by their very nature are problematic. A building is used to enshrine the legacy of one person. Yet a home always has more than one person deeply involved in its history. There are all the owners of the land it sits on. There are the designers and builders of the house and furnishings. There’s the rest of the family, and perhaps servants or enslaved people, who ensure the house and its inhabitants are cared for. There’s also an entire community surrounding it. Ignoring the contributions of so many others, usually women and other lesser-status individuals, distorts history and risks suggesting that the honored individual—like James Madison—existed in some sort of vacuum where his genius flowered. Certainly, had he been responsible for growing, harvesting, and preparing his own meals; making, mending, and washing his own clothes; caring for livestock and undertaking building maintenance Madison would have had little time to study history and law and pen the Constitution. The power inequities of the home were, of course, also evident in the larger society. Before the 1600s, dining tables were merely boards laid across trestles or diners’ knees. Over time, the word “board” came to also mean the meal itself (thus the terms “boardinghouse,” “boarders,” and “room and board”). People sat on plain benches and when chairs came into more general use in the seventeenth century they were designed to convey authority, with the man of the house seated in one while the rest of the household sat on benches. That’s why today the person in charge of a company is the chair(man) of the board. Women and lesser-status people have been serving people at the board, cleaning up the board, not allowed to sit at the board, sitting below the board, for a very long time. Symbols and words matter, and as Bill Bryson points out in At Home: A Short History of Private Life, it’s a little odd that our governance structures recall the dining arrangements of medieval peasants. It’s also odd that we’ve retained the authority structures of boards as well. While diversity of employees and boards is finally being recognized as a positive in the corporate world, including for the bottom line, women and minorities remain woefully underrepresented. (Dig into the numbers here.) Boards are about power, and power is often about money. Did the Montpelier board get cold feet at the idea of sharing power? Did a wealthy donor threaten not to contribute? To people who are afraid of losing power, change comes particularly hard. We won’t get into the Supreme Court “bench.” |

AuthorHeidi Hackford explores how past and present intersect. Archives

November 2023

Categories |