|

The DNA of Ancestry

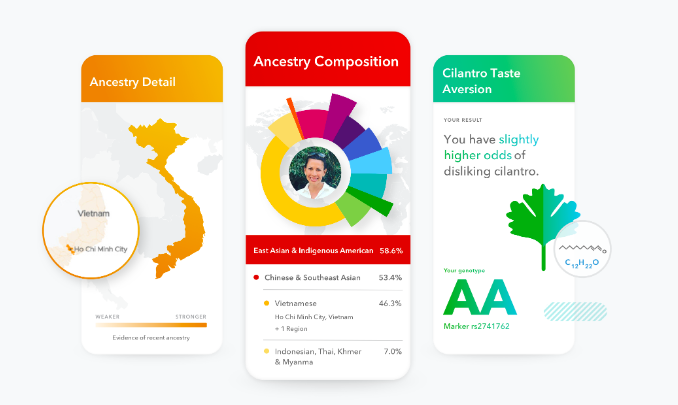

When my dad turned 80 a few years ago, I gave him a 23andMe genetic test for fun. His DNA report said he is 100% northern European, primarily from the Alsace region of Europe, an area along the Rhine River that has fluctuated between German and French control in the last 150 years. The results matched what we already knew about his ancestry from family lore—there were no surprises except for a small but significant percentage of DNA from the Netherlands. For others, genetic testing can be full of surprises. One woman I know learned that the man she calls her father is not actually her father. After taking a DNA test, she discovered her biological father’s family and a number of half-siblings. When confronted with this information, her mother reluctantly admitted to a long-ago affair. Another acquaintance told me she knew she was adopted but not that she also has a number of siblings, which she discovered when she took a test. After the initial shock, these women now appreciate their new connections. For a historian, the idea that we could possibly discover lost or unknown linkages between people and places through a simple test is exciting. We spend a lot of time trying to find tiny bits of information in vast archives, imagining the stories that might lie behind an artifact, and dealing with frustration at the limited documentary sources remaining or photographs that no one thought to label. Taking the guesswork out of our origins feels too good to be true. And, to some degree it is. Because there are other ramifications of the technology to consider. Think about the people whose DNA helps to capture criminals who left their own DNA behind at a crime scene. Revelations about those kinds of shared origins could hardly be celebrated beyond appreciating that a criminal might have walked free if not for the test. For Black Americans, DNA testing can be problematic. DNA tests like those used at 23andMe use reference groups—people alive today who share genetic sequences common to people of a certain area—to deliver results. A function of who is taking the tests, the reference groups are much more robust for people from North Atlantic European populations than for those from other parts of the world. For people of African descent, the reference groups are sparse. But, due to historic abuses by government and health officials, such as the notorious Tuskegee syphilis experiments, Black Americans may be reluctant to participate. This means that they won’t have access to the health data encoded in their DNA that could provide helpful—even potentially life-saving—information. Further, receiving a DNA report that includes percentages of white DNA that might be the result of coercion or rape, could be difficult to deal with emotionally. Recently, two Stanford researchers developed a model to estimate the average number of genealogical ancestors from African and European source populations for a random African American individual born between 1960–1965. They discovered that, on average, there would be 314 African and 51 European ancestors. (Read the article here.) It’s important to understand that all DNA information is probabilistic. That means that even if your DNA test says you are likely to have curly hair, you may not. While DNA revelations can still be exciting, perhaps we should think about what these tests seem to reveal with a deeper understanding of what they don’t. Image: 23andMe ancestry report homepage example.

0 Comments

|

AuthorHeidi Hackford explores how past and present intersect. Archives

November 2023

Categories |