|

Student loan forgiveness as racial justice

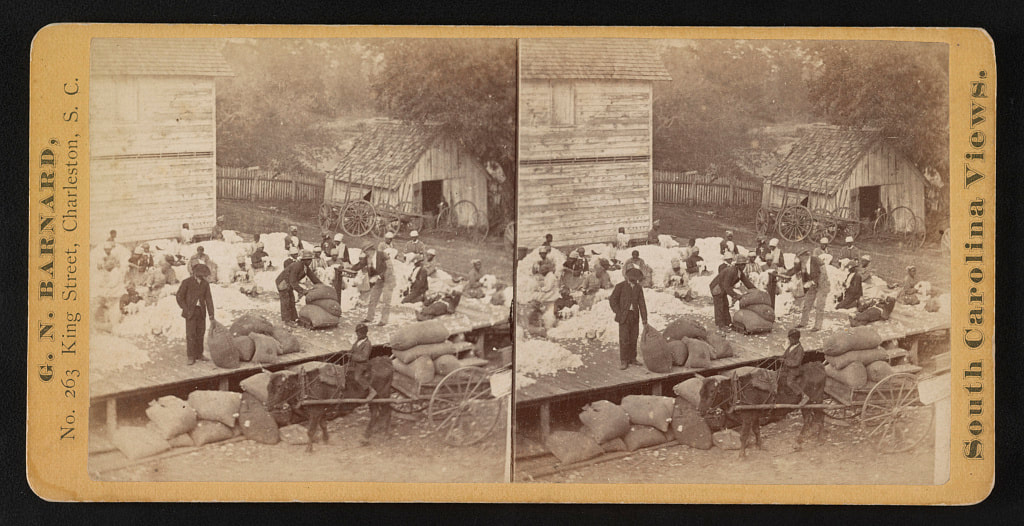

President Biden recently announced a new plan to forgive $10,000 of federal student loan debt for each borrower. For those concerned about the disproportionate share of debt held by people of color, particularly Black women, who owe the most, this was welcome news and a matter of racial justice. Black students have less generational wealth to draw on than White students to pay the bills for higher education. Criticisms of the debt forgiveness plan are many, but some seem strikingly familiar. That it’s too expensive, an example of big government overreach, and will encourage people to be lazy were arguments used 150 years ago by President Andrew Johnson when he rejected plans to aid the newly emancipated slaves. Historian Eric Foner’s classic work, A Short History of Reconstruction (1990), delves deeply into the time immediately following the Civil War, when many of the conditions that created today’s wealth gap were formed. It’s a complicated story, but by the time Reconstruction ended in 1877, Black people’s status as an underclass had been firmly established. When the Civil War ended, emancipated slaves and many Union supporters believed that it was only fair they should receive portions of the land they had labored on, unpaid, for generations. Congress authorized the Freedmen’s Bureau to divide abandoned and confiscated Southern lands into 40-acre plots. This redistribution would have weakened the power of the plantation class and provided the former slaves with a means to earn their own livings. However, Johnson ensured it never happened. In areas where the process had already begun, Black families were displaced and the land was returned to its former owners. Former Confederates worked to restore as much of the slave system as they could. Many Northerners, even those who advocated for the freedmen, assumed the easiest way to restore the South’s economy and transition to a system of free labor was to keep the ex-slaves on the plantations but pay them wages. To ensure that this would happen, Whites refused to rent or sell land to Blacks. In urban areas, only low-wage menial labor was available and Black families were segregated into squalid shantytowns. States passed Black Codes that required ex-slaves to sign restrictive labor contracts with severe punishments for breaking them, including involuntary plantation labor. Apprenticeship laws required black minors to work for planters without pay. Men, women, and children were whipped, beaten, and hung for “insolence” or “insubordination” as defined by the Codes and interpreted by Whites. Black homes and communities were burned and destroyed. Foner says: “Freedmen were assaulted and murdered for attempting to leave plantations, disputing contract settlements, not laboring in the manner desired by their employers, attempting to buy or rent land, and resisting whippings. . . . Charges of “indolence” were often directed not against blacks unwilling to work, but at those who preferred to labor for themselves.” (pgs. 53, 60) Whites also joined together to fix wages at low rates, evicted Black laborers without pay, and refused to give ex-slaves their share of the crop. The freedmen had no recourse with all-White police and judicial systems. They were barred from receiving poor relief and using parks and schools, despite paying taxes to support public services. Yet, despite the perpetual threat of violence and the difficulties of meeting their basic needs under these conditions, emancipated slaves spent their hard-earned money and limited time avidly pursuing education. Outlawed during slavery (90% of Blacks were illiterate when the Civil War began), education was seen as central to the meaning of freedom. Children and adults flocked to the schools set up in churches, basements, warehouses, and homes. In New Orleans and Savannah, emancipated slaves studied on the sites of former slave markets. Forgiving student debt is the least we can do. Image: Laborers, including ex-slaves, preparing cotton for gins, on Alexander Knox's plantation, Mount Pleasant, near Charleston, S.C. during Reconstruction [1874]. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

0 Comments

|

AuthorHeidi Hackford explores how past and present intersect. Archives

November 2023

Categories |