|

Deep Fakes Are Nothing New In History

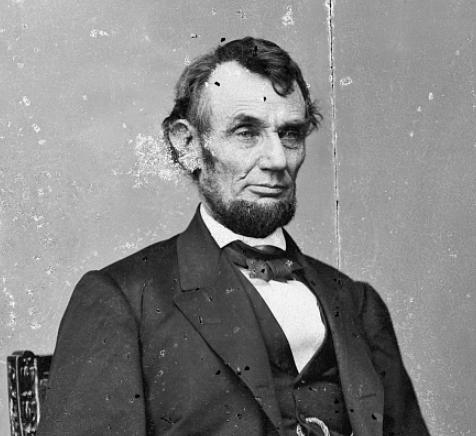

I had headshots taken recently to use for publicity photos. My target market is book clubs, and I plan to make myself available on Zoom to groups that might want to discuss the novel with me in person, so my goal was to look approachable. I met a friend who’s a professional photographer and we spent a half hour snapping photos. Afterward, he whittled down a hundred images to four and touched them up, removing a white truck in the background and giving my face a virtual spa treatment. This process was very different 150 years ago, when people had to sit with faces frozen until the exposure set and didn’t have the luxury of a dozen do-overs. But are my touched up and curated photos really anything new? When I worked in the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library archives, we had two copies of a photograph of Wilson meeting with his cabinet after one of many strokes he suffered while in office. In one, there is a white cane propped on his chair. In the other, the cane has been removed, erasing the question of his disability. World leaders used altered photographs to change history, removing people as they fell out of favor. Photographers sometimes stitched heads on different bodies in the darkroom. This impulse to convey an “adjusted” reality is probably an age-hold human impulse. Art historians detect alterations in paintings made centuries ago. Documents, too, can be preserved or destroyed or changed. The writers themselves may have applied their own literary “airbrush” as they wrote, filtering thoughts and feelings. The famous correspondence between aging founding fathers Thomas Jefferson and John Adams was calculated to burnish their images for the historical record. They were well-aware that their letters would be read for generations. These days, everyone knows photos can be “Photoshopped.” Anyone active on Facebook knows that people curate the images they share, and kids can make deep fake videos with their iPhones that are only going to get better as the technology improves. Most of us are becoming more skeptical of what we see, thinking like historians and requiring evidence from multiple sources before we accept something as true. Although there will always be some who blindly (ha ha!) see only what they want to see. So, can we trust our eyes at all when we look at artifacts from the past? I like to think there is some kind of essential truth buried beneath deliberate interventions, an authentic humanity that we can feel if we look deeply and really see, with our hearts as well as our eyes. Consider the photograph below of Abraham Lincoln, still mourning the death of his young son during the Civil War. Lincoln often disparaged his personal appearance. When debate opponent Stephen Douglas accused him of being two-faced, he responded, “If I had another face, do you think I’d wear this one?” But, although many thought him ugly, others who met him in person felt like Lillian Foster that “the good humor, generosity and intellect beaming from [his face], makes the eye love to linger there until you almost fancy him good-looking." Or, the Utica newspaperman who reported, “After you have been five minutes in his company you cease to think that he is either homely or awkward.” Look deeply at the photo of Lincoln above. What do you see? Image above: Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

0 Comments

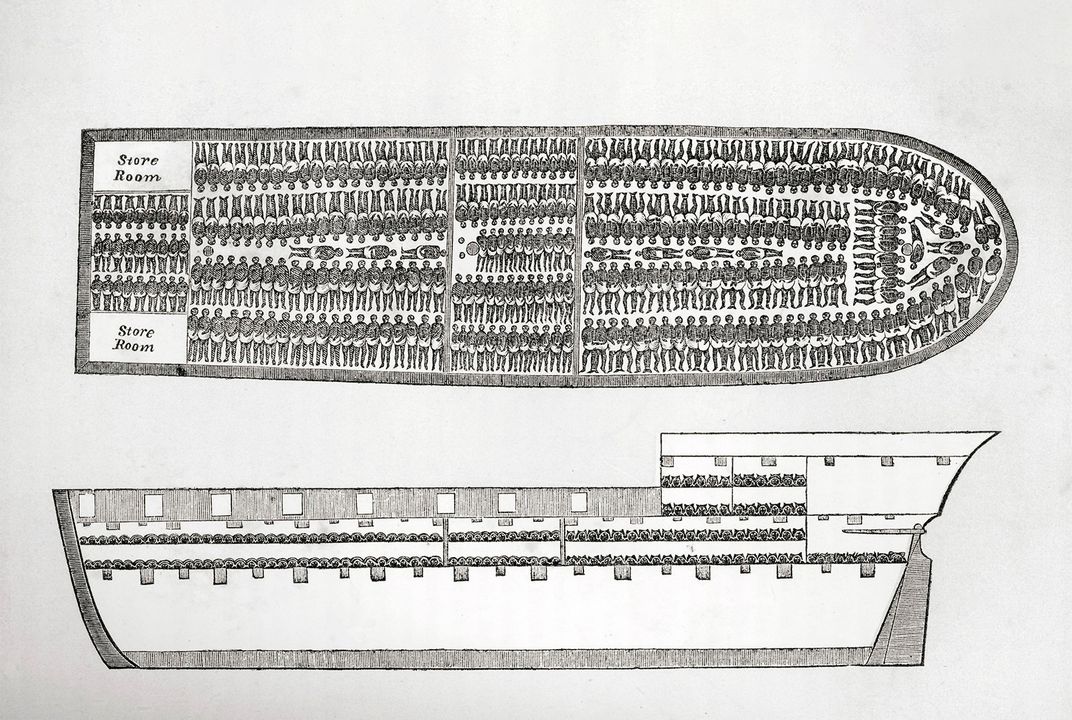

Embodied History Recently, as I was looking through some family history files during a visit to my parents, my sister showed me an elaborate family tree she’d made for a college health class. Along with birth and death dates there were notations about the causes of death that ranged from heart disease and tuberculosis to accidental drowning and falling out of a tree. That one detail under each name made these people real to me in a way they had never been before. I felt a weight on my heart. Often when I’m reading history, I imagine a narrative in my mind that unfolds like I’m watching a movie, the places like sets, the people like actors. But if you’ve ever run into a celebrity in the real world, you may have experienced how they first seem somehow familiar followed quickly by recognition and a little shock that they don’t look like they do on the screen. Instead, they actually look like a normal person. You can see them, human-to-human. I had a similar shock of recognition when I was reading a book that described the typical Civil War soldier as 5’8” tall and weighing about 140 pounds. I am that same height and just a bit lighter. I know what it feels like to move through the world in a body like mine. My early interest in history may even have been sparked by imagining the physicality of those who came before. When I was about six or seven years old, my father, an avid history buff, took the family on a Saturday trip to see Old Fort Niagara. Dating from before 1726 and rich with history, I remember being struck by one thing: the bunks looked like they could barely accommodate someone my size, let alone a full-grown man. Some twenty years later, the sight of my grandmother’s wedding dress elicited a similar aghast reaction. There was no way that I, or any of my female cousins, could fit into that dress (see photo below). One of my friends told me he was inspired to pursue a graduate degree in history because of a particular experience in college. To try to bring home some of the horrors of the Middle Passage—the Atlantic crossing for millions captured and sold into slavery—the professor used a diagram like that below to measure out spaces on the floor. For the duration of the class, the students laid flat on the ground, crammed close and barely able to move. It was an hour that changed my friend’s life. This kind of experiential learning probably couldn’t happen in a college classroom today, but those of us who choose to can find plenty of opportunities to re-enact a part of history, to dress up in period clothing and, literally, walk in someone else’s shoes. If every hour of every day we all felt deep down in our bones that we are one small part of the continuum of the human race—that we are not exceptional actors on a stage—would we treat each other and the world differently? Image above: How slaves were packed into a ship for the Middle Passage. See the story in which this image appears in the Smithsonian Magazine. |

AuthorHeidi Hackford explores how past and present intersect. Archives

November 2023

Categories |