|

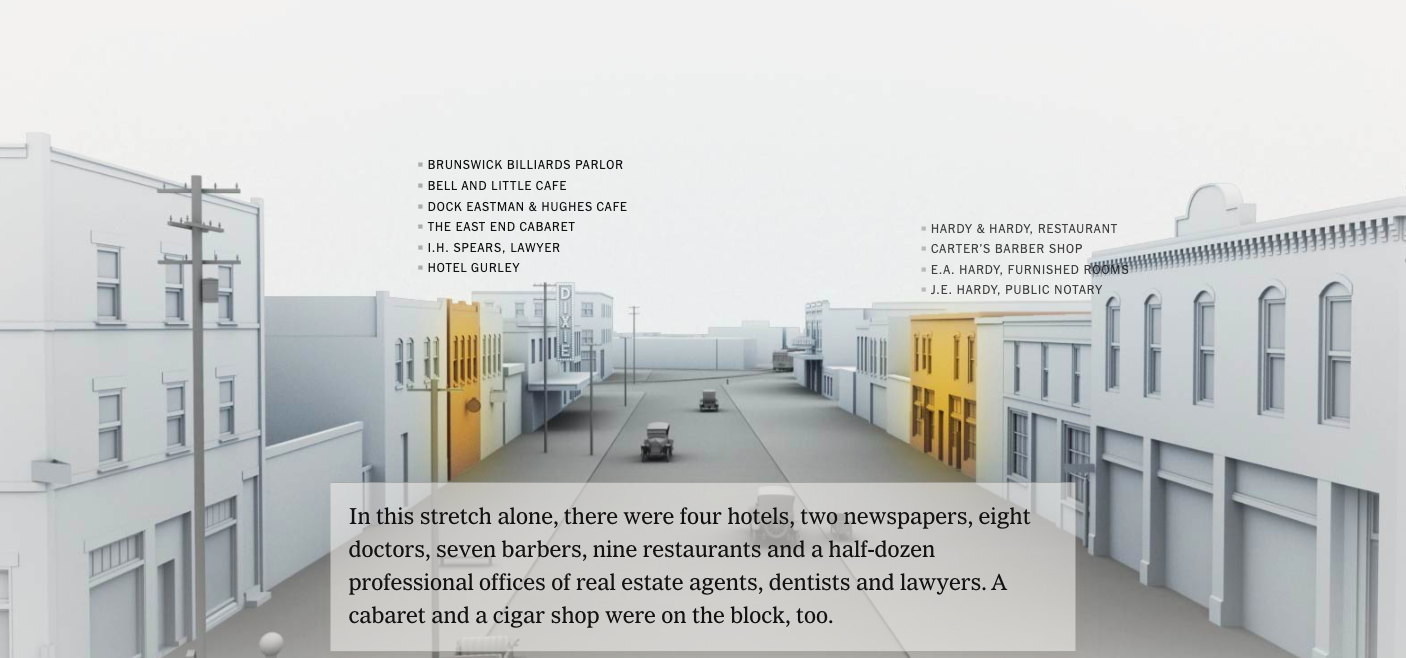

Finding Black people and places in history Recently, I learned that there used to be a thriving 19th century village just a couple of miles down the road. There’s nothing left of Purissima now but a cemetery and a cypress grove. When the railroad left, the town died. Reading about this “lost” village reminded me of the vanished Vinegar Hill, near where I lived in Charlottesville, Virginia (see image above). Vinegar Hill was a thriving Black community razed in 1965. The city’s largest Black neighborhood and a hub of social life, 139 homes and 30 Black-owned businesses and a church were destroyed in the name of “urban renewal.” The land was valuable, and the city was eager to redevelop it into shops and apartments . . . for White people. This kind of destruction was the rule more than the exception in the rapidly growing post-WWII United States. In the last few years, some cities have explored efforts to compensate residents and their descendants for property taken by eminent domain for public projects (read more). In my hometown of Buffalo, NY, I often traveled on the Kensington Expressway, passing large and stately homes butting up to the traffic. Recently called a “mistake” by NY’s former governor, the road destroyed the thriving Black communities around Humboldt Parkway—part of the beautiful park system designed for the city by Frederick Law Olmstead. Humboldt Parkway, yesterday and today. Of course, Black communities were also lost through violence and destruction. Suppressed in the papers of the time but later referred to as a “race riot,” what happened in Oklahoma 100 years ago has been more accurately renamed “the Tulsa race massacre.” Following an incident between a White woman and young Black man in an elevator (it is believed he may have stepped on her shoe), White vigilantes burned more than 1,200 homes and killed hundreds. Claiming they feared that word of the young man’s arrest would draw unruly Blacks from the surrounding country and nearby neighborhoods, they preemptively annihilated what was known as “the Black Wall Street.” You can walk through the recreated lost community in this interactive NYT article. The narrative used in Tulsa was honed during slavery. In Tumult and Silence at Second Creek (1995), historian Winthrop D. Jordan, explores a slave conspiracy in Mississippi in 1861. Hearing of the outbreak of the Civil War, a number of slaves in a wealthy, established plantation community allegedly plotted to kill their masters and take the White women. Fearing the unrest would spread, dozens of slaves were questioned and summarily executed by an extra-legal “Examination Committee” of slave owners. These slaveowners gave up their legal right to be compensated for their executed slaves in the name of secrecy, fearing that it might inspire other uprisings or provide ammunition to the Northern cause. One woman wrote to her niece: “It is kept very still, not to be in the papers . . . don’t speak of it only cautiously.” Although the houses where the Second Creek slaves lived have long disappeared, many of the mansions still stand. Some are tourist attractions.

***To see what communities have been lost in your hometown, google “urban renewal Black neighborhoods [YOUR CITY].” Main image: Vinegar Hill in the 1930s. Read the story.

1 Comment

|

AuthorHeidi Hackford explores how past and present intersect. Archives

November 2023

Categories |