|

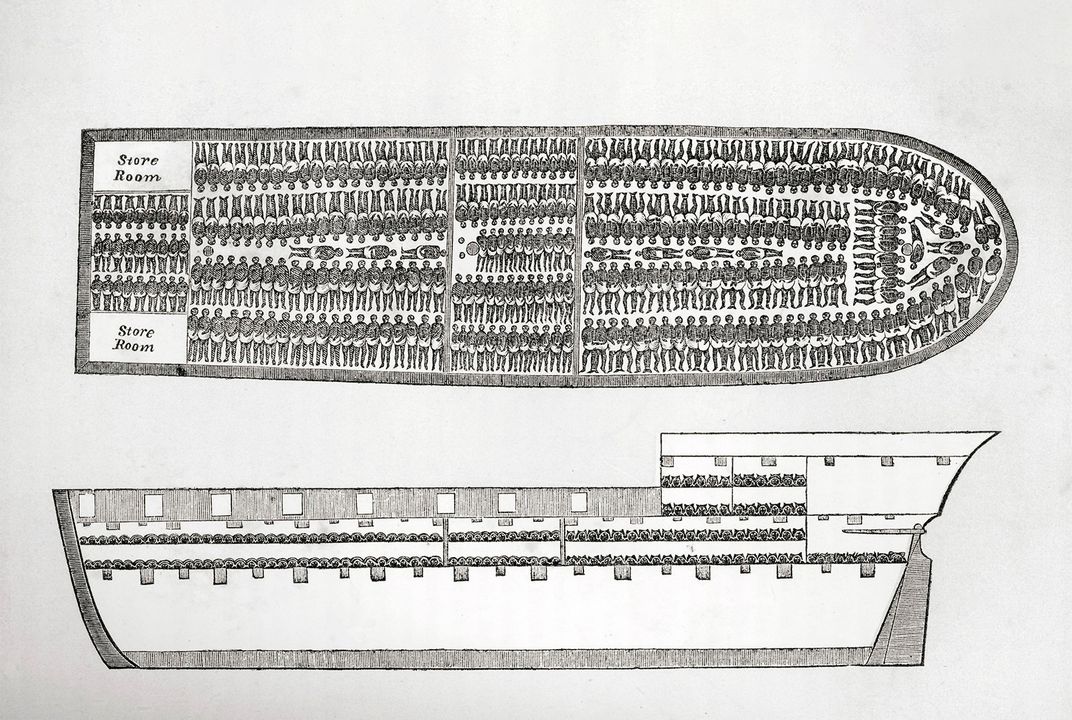

Embodied History Recently, as I was looking through some family history files during a visit to my parents, my sister showed me an elaborate family tree she’d made for a college health class. Along with birth and death dates there were notations about the causes of death that ranged from heart disease and tuberculosis to accidental drowning and falling out of a tree. That one detail under each name made these people real to me in a way they had never been before. I felt a weight on my heart. Often when I’m reading history, I imagine a narrative in my mind that unfolds like I’m watching a movie, the places like sets, the people like actors. But if you’ve ever run into a celebrity in the real world, you may have experienced how they first seem somehow familiar followed quickly by recognition and a little shock that they don’t look like they do on the screen. Instead, they actually look like a normal person. You can see them, human-to-human. I had a similar shock of recognition when I was reading a book that described the typical Civil War soldier as 5’8” tall and weighing about 140 pounds. I am that same height and just a bit lighter. I know what it feels like to move through the world in a body like mine. My early interest in history may even have been sparked by imagining the physicality of those who came before. When I was about six or seven years old, my father, an avid history buff, took the family on a Saturday trip to see Old Fort Niagara. Dating from before 1726 and rich with history, I remember being struck by one thing: the bunks looked like they could barely accommodate someone my size, let alone a full-grown man. Some twenty years later, the sight of my grandmother’s wedding dress elicited a similar aghast reaction. There was no way that I, or any of my female cousins, could fit into that dress (see photo below). One of my friends told me he was inspired to pursue a graduate degree in history because of a particular experience in college. To try to bring home some of the horrors of the Middle Passage—the Atlantic crossing for millions captured and sold into slavery—the professor used a diagram like that below to measure out spaces on the floor. For the duration of the class, the students laid flat on the ground, crammed close and barely able to move. It was an hour that changed my friend’s life. This kind of experiential learning probably couldn’t happen in a college classroom today, but those of us who choose to can find plenty of opportunities to re-enact a part of history, to dress up in period clothing and, literally, walk in someone else’s shoes. If every hour of every day we all felt deep down in our bones that we are one small part of the continuum of the human race—that we are not exceptional actors on a stage—would we treat each other and the world differently? Image above: How slaves were packed into a ship for the Middle Passage. See the story in which this image appears in the Smithsonian Magazine.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHeidi Hackford explores how past and present intersect. Archives

November 2023

Categories |