|

“It was the eighteen hundreds; that’s how those places functioned. They used slaves. It’s not pretty dear, but it’s history,” says Debbie’s father when she confronts him with a DNA test showing that they’re related to hundreds of Black people, descendants of their slaveholding ancestor.

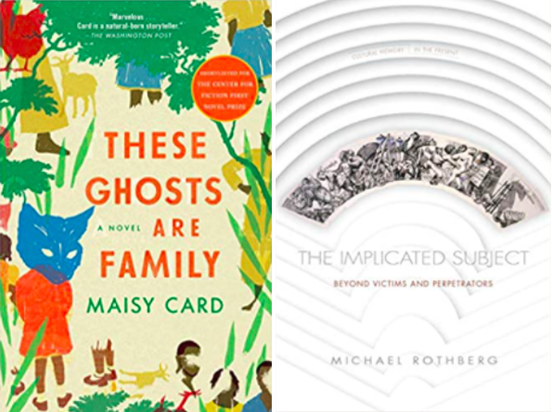

In Maisy Card’s These Ghosts Are Family (2020), Debbie’s elderly father wants to keep the family history private, not only because it is shameful, but because he fears that with “all this talk about reparations” someone might sue them. Twenty-something Debbie wants to face up to the ugliness, to not be one of those white people. She’s ready to share Harold Fowler’s diary with a Black history professor. But the plantation owner’s record of his torture and rape of his enslaved workers begins to haunt Debbie. UCLA professor Michael Rothberg’s book The Implicated Subject (2019) offers a helpful way to explore historical fiction that deals with difficult topics like slavery. Rothberg argues that we need a new vocabulary to talk about our relationship to historical violence and contemporary inequalities beyond just perpetrators and victims. The term “implicated subject” includes the roles of enablers, beneficiaries, and perpetuators. Debbie and her father are “implicated” in past injustices by benefiting from slavery and perpetuating systemic racism. For example, the family wealth, built on Jamaican slavery, pays the rent for Debbie’s expensive New York City apartment while she earns $12 an hour as an intern at an art museum where there is only one Black curator. As Debbie becomes immersed in the horrors of the diary, she begins to have nightmares where she takes the place of the enslaved women, literally feeling their pain and waking up bruised and screaming. She begins “to wonder whether, since Harold had put so much evil in the world, she could afford to be neutral. She had to atone.” On a trip to the site of the old plantation, her atonement takes the form of symbolically killing Harold. Wading into the river, she tears the pages out of his diary and lets them float away, hearing his voice in her head “until she heard only gurgling, the sound of his throat filling with water as he drowned.” But Debbie’s act of atonement did not help the real historical victims. In identifying with them, rather than recognizing her relationship to slavery as an implicated subject, Debbie actually becomes a perpetrator of present-day white supremacy. She protects the slaveholder and his White descendants by destroying the documentation of his wrongs, removing it from the historical record and denying Black descendants’ knowledge of their genealogy. As readers and writers of fiction that deals with historical violence and injustice, we are implicated subjects. Unlike Debbie, however, we must be clear-eyed about our relationship to the past and very careful about how we share its stories because, Rothberg warns, the “implicated subject is a transmission belt of domination.” Faulkner was right: the past is not dead.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHeidi Hackford explores how past and present intersect. Archives

November 2023

Categories |