|

Dis-ease about illness yesterday and today

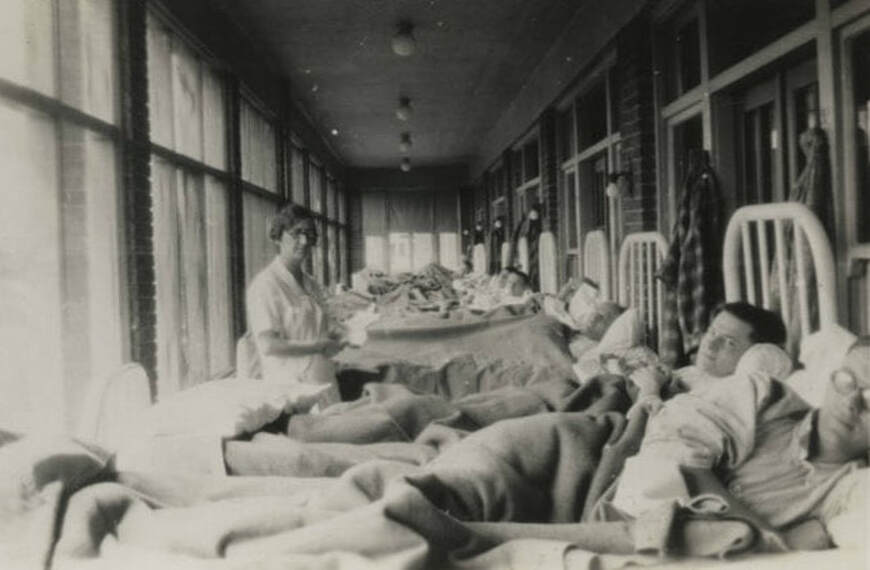

There was a sleeping porch attached to my bedroom in the house I rented in Washington, DC, during graduate school. Around the turn of the 20th century, the presence of this architectural feature was a clear indication of respiratory problems in a family. Houses were altered to give tuberculosis sufferers access to fresh air. I was struck by the commonalities between the social and cultural response to COVID and TB when I re-read a book by one of my dissertation advisors, Katherine Ott’s Fevered Lives: Tuberculosis in American Culture since 1870. Can exploring these similarities help us to connect emotionally—both with our forebears and with our neighbors? Like COVID, TB can affect many parts of the body but primarily attacks the lungs. It is endemic in the U.S. and at its peak in the mid-19th century killed 1 out of 5 adults. A 1904 mortality rate of 200 deaths per 100,00 mirrors the latest COVID surge. Unlike COVID, TB is infectious rather than contagious—it’s spread by airborne germs (mycobacterium), and usually ran its course in two and a half to five years. Some patients recovered, many did not. Like COVID treatments before the vaccine, TB treatments weren’t very effective until the mid-20th century, when chemotherapy became available. From 1920 to 1950, collapsing a lung on purpose to “rest” it was the most common form of treatment; doctors might also remove some ribs. Quack serums and antitoxins made from turtles and horses bring to mind the use of the deworming drug ivermectin to treat COVID. Perhaps the equivalent of injecting bleach for COVID, one TB doctor argued that shaving resulted in mass deaths; he believed that a beard protected the throat and lungs. (So much for the women!) Like Anthony Fauci, earlier physicians warned that TB was everywhere, and no one was safe. They advocated social distancing and told people to avoid shaking hands and kissing. TB was erroneously believed to be transmitted on money, pets, and library books (remember wiping down our groceries?). Public drinking buckets and cups were replaced with water fountains. Disinfecting everything was recommended, and patients’ belongings were burned when they died. Merchants and businesspeople, perhaps conflating their self-interest with science, argued that quarantine was the wrong response to TB. These “anti-contagionists” pushed back against public health “sanitationists” and rejected the germ theory of disease, even after it had been verified in 1880; it did not become widely accepted in the U.S. until 1900. Those who contracted TB were told to isolate. For some, this meant leaving friends and family to travel to supposedly more healthful climates to live in tents and cabins in places like Southern California, Asheville, NC, and the Adirondacks. For those who could afford it, sanitariums offered a stringent “rest cure.” During the pandemic, where I live in the San Francisco Bay area, there has been an exodus (of those who can afford it) to Lake Tahoe, beach towns, and less-populated states. Early in the 20th century, Dr. J.H. Landis noted: “Self-preservation demands a radical revision of the definition of personal liberty in order that future generations shall not come into the world chained to a corpse; it demands a radical change, giving the state the power to correct an environment that has left its wrecks through a series of generations.” The police power of the state was justified to protect the public. Reminiscent of states like Rhode Island that turned away cars with New York license plates at checkpoints early in the COVID pandemic, people were banned from crossing state lines. And, like today’s airlines, officials could forcibly remove infected people from a community if they were believed to be recklessly spreading infection. Fear and anxiety about disease is nothing new—it’s as old as humanity. So, apparently, are the ways in which we respond. Image credit: Patients on a "sleeping porch" at Irene Byron Tuberculosis Sanatorium, c. 1927-1928. Ball State University. University Libraries. Archives and Special Collections

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorHeidi Hackford explores how past and present intersect. Archives

November 2023

Categories |